Finding Women in the Historical Record

Posted by Cait Coker

When I first started studying and then teaching the history of the book, I was struck by the absence of women in the conventional histories and reference books. The concept of women in book history as a field has until (very) recently been rather limiting; examinations of significant volumes like The Oxford Companion to the History of the Book omit even the possibility of “women” as an entry, to say nothing of the sparse notations in indices or the lack of space in most disciplinary readers (Levy and Mole’s 2017 Broadview Introduction to Book History is a notable exception, with its brief bibliography on women and the book as an appendix in the back) and syllabi.

My search for women in the scholarship became a systematic hunt for articles and the occasional book, all of which were subject to the vagaries of cataloging and tagging that only sometimes acknowledged the “women” part of women printers, women booksellers, and so on. On the plus side, this led to our Little Bib That Could, but on the negative side, it led to the dispiriting realization of how easily meaningful scholarship can be “lost” through its inaccessibility or its lack of citations (and remember, per Sara Ahmed, that citations are political acts).

As we all know by now (I hope), women have been printing alongside men since the invention of the printing press, but their stories have been comparatively neglected in the “big” narratives repeated in textbooks that focus only on familiar figures like Gutenberg, Caxton, Franklin, and so on. Women printers—and papermakers, booksellers, etc.—are more often relegated to footnotes, the occasional passing mention of a name, and a more often generic mention of “women and men in the trades,” thus giving the impression that their presence is unusual or passing in the broader context of the history of the book.

On the contrary, Maureen Bell’s 1983 A Dictionary of Women in the London Book Trade 1540-1730 lists hundreds of women in the city of London alone during a period encompassing less than two centuries. But Bell’s text is an unpublished thesis; even if the knowledge itself is out there more broadly, obtaining a copy of Bell is more difficult without a Proquest subscription or a solid interlibrary loan system. More recent books, like Helen Smith’s magisterial ‘Grossly Material Things’: Women and Book Production in Early Modern England, among others, can too easily get lost in the shuffle of academic press production. (That said...go read it, because it is awesome.)

My frustration with secondary sources led to revisiting primary sources. When I started looking for women in the historical record, I was struck by how very present—even omnipresent—they were. Women’s names appear on the imprints of title pages, in accounting books and contracts, in images of workers sorting rags and in the background of printing shops. Their consistent erasure and diminishment in most of mainstream scholarship is therefore at complete odds with their actual presence in books and records.

This erasure is not, I think, necessarily intentional, but it does show that the assumed viewpoint of the book historian tends to the masculine default. In other words, it’s simply assumed that women were not present in the book trades (the homosocial bonds being strong), or if they were they were unusual (widows), or they were family members whose labor included as part of the pre-industrialized family business (sisters, daughters, wives), or the women were present but it didn’t mean they were “working” in the same way that men were (widow printers who weren’t “really” printing), or...or...or… With apologies to Joanna Russ: “She printed it, but…”

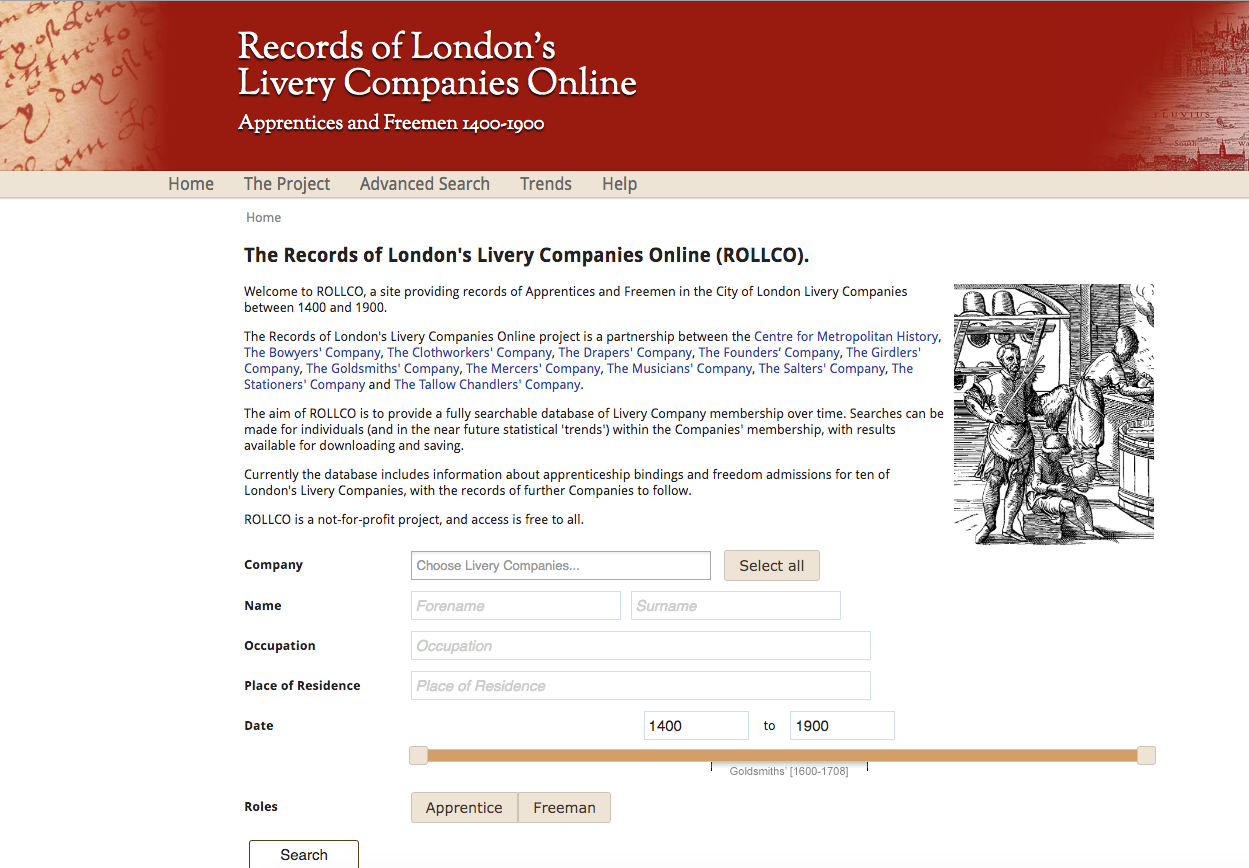

A further hiccup to locating women in primary resources is the discoverability of such data. For example, try searching imprints in Worldcat; depending on various institutions’ cataloging practices, names that appear with only initials may or may not have the full names of printers (or authors) in the actual item record. Accessibility in other databases is similarly fraught, depending on whether its designers thought gender a useful topic to include, as well as on access to those resources themselves. Three incredibly useful open-access tools are ROLLCO, BBTI, and the WPHP.

Records of London’s Livery Companies Online

The Records of London’s Livery Companies Online (ROLLCO) includes gender as a limiter in their Advanced Search options. Sorting for women in the Stationers from 1400-1900 produces 902 records, and limiting to women in the years 1600-1700 leads to 207 records. Not all Stationers were printers, though perforce all* printers were required to be Stationers. (*Actually it’s a bit messier than that depending on time period and legal hijinks, but...you get the idea.)

British Book Trade Index

In contrast, another useful database, the British Book Trades Index (BBTI) does not allow for sorting by gender, but you can do searches for first names and sort by specific trades. For instance, a sample search for “Mary” and a limiter of “printer” returns 158 results. However, some of its data is...problematic, to say the least (the seventeenth-century printer Mary Simmons is identified as having only one imprint when, in fact, she had at least 42), but each entry cites additional resources for further research that can be of great help when starting out.

These two sources won’t get you everywhere you need to go, obviously, but their accessibility and usability make them great tools for working on your research as well as working with students. And always remember: check in with your friendly librarians at your institution to see what else they might have to hand, as you might be surprised what they can get access to for your classes (or can make applications for in their administrations if they know that faculty and students need/want those resources).

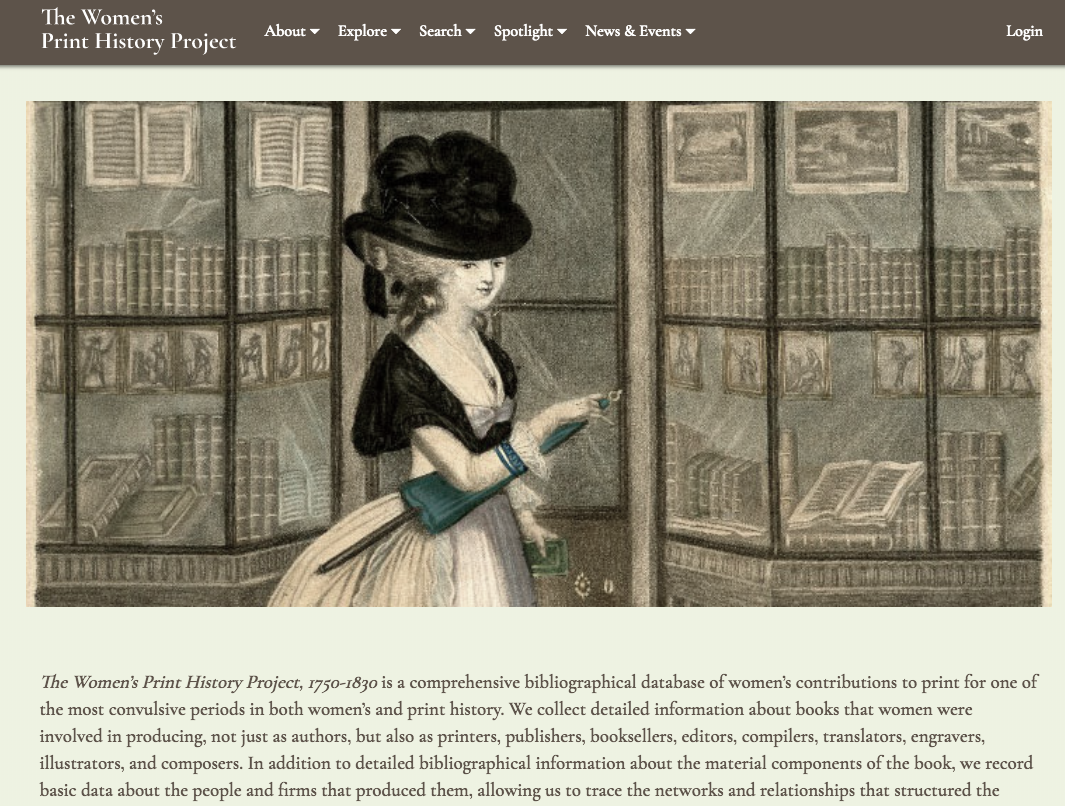

Women’s Print History Project

Lastly, I’ll plug that at a recent symposium Michelle Levy, Kate Ozment, and Kandice Sharren put together a worksheet of sources on finding women in the book trades in the very long eighteenth century. It’s available here. Levy and Sharren are still working on their Women’s Print History Project which has information about a lot of women in the book trades in England from 1750-1830.

Do you have other handy resources you have come across that make use of historical records? Let us know in the comments!

About the Author

Cait Coker is Associate Professor and Curator of Rare Books and Manuscripts at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and will soon receive her doctoral degree in literature from Texas A&M University. Her current projects include journal articles on women's labor in the book trades in seventeenth-century England. She also frequently publishes on SFF and popular culture including editing the forthcoming collection The Global Vampire in Popular Culture. Contact her at: cait.coker (at) gmail (dot) com.

-

October 2022

- Oct 16, 2022 Teaching in the Maker Studio Part Two: Safety Training and Open Making

- Oct 16, 2022 Teaching Book Forms

- Oct 16, 2022 Teaching Letterpress with the Bookbeetle Press

-

September 2022

- Sep 24, 2022 Making a Scriptorium, or, Writing with Quills Part Two

- Sep 16, 2022 Teaching Cuneiform

- Sep 4, 2022 We're Back! Teaching Technologies of Writing

-

June 2020

- Jun 1, 2020 Black Lives Matter

- May 2020

-

April 2020

- Apr 1, 2020 Teaching Materiality with Virtual Instruction

- March 2020

-

February 2020

- Feb 1, 2020 Making the Syllabus Zine

-

January 2020

- Jan 1, 2020 Teaching Print History with Popular Culture

-

December 2019

- Dec 1, 2019 Teaching with Enumerative Bibliography

-

November 2019

- Nov 1, 2019 Finding Women in the Historical Record

-

October 2019

- Oct 1, 2019 Teaching in the Maker Studio

-

September 2019

- Sep 1, 2019 Graduate School: The MLS and the PhD

-

August 2019

- Aug 1, 2019 Research Trips: Workflow with Primary Documents

-

July 2019

- Jul 1, 2019 Research Trips: A Beginner's Guide

-

June 2019

- Jun 1, 2019 Building a Letterpress Reference Library

-

May 2019

- May 1, 2019 Teaching Manuscript: Writing with Quills

-

April 2019

- Apr 1, 2019 Why It Matters: Teaching Women Bibliographers

- March 2019

-

February 2019

- Feb 1, 2019 Roundup of Materials: Teaching Book History

-

January 2019

- Jan 1, 2019 Building and Displaying a Teaching Collection

-

December 2018

- Dec 1, 2018 Critical Making and Accessibility

-

November 2018

- Nov 1, 2018 Teaching Bibliographic Format

-

October 2018

- Oct 1, 2018 Teaching Book History Alongside Literary Theory

-

September 2018

- Sep 1, 2018 Teaching with Letterpress

-

August 2018

- Aug 1, 2018 Teaching Manuscript: Circulation

-

July 2018

- Jul 1, 2018 Setting Up a Print Shop

-

May 2018

- May 1, 2018 Teaching Manuscript: Commonplace Books

-

April 2018

- Apr 1, 2018 Getting a Press

-

March 2018

- Mar 1, 2018 Teaching Ephemera: Pamphlet Binding

- February 2018