Research Trips: A Beginner's Guide

Posted by Kate Ozment. This is part one of a series on research trips. Part two will be posted this summer and will cover archival workflow. Part three will be posted this fall and show how to use material from archival documents in the classroom.

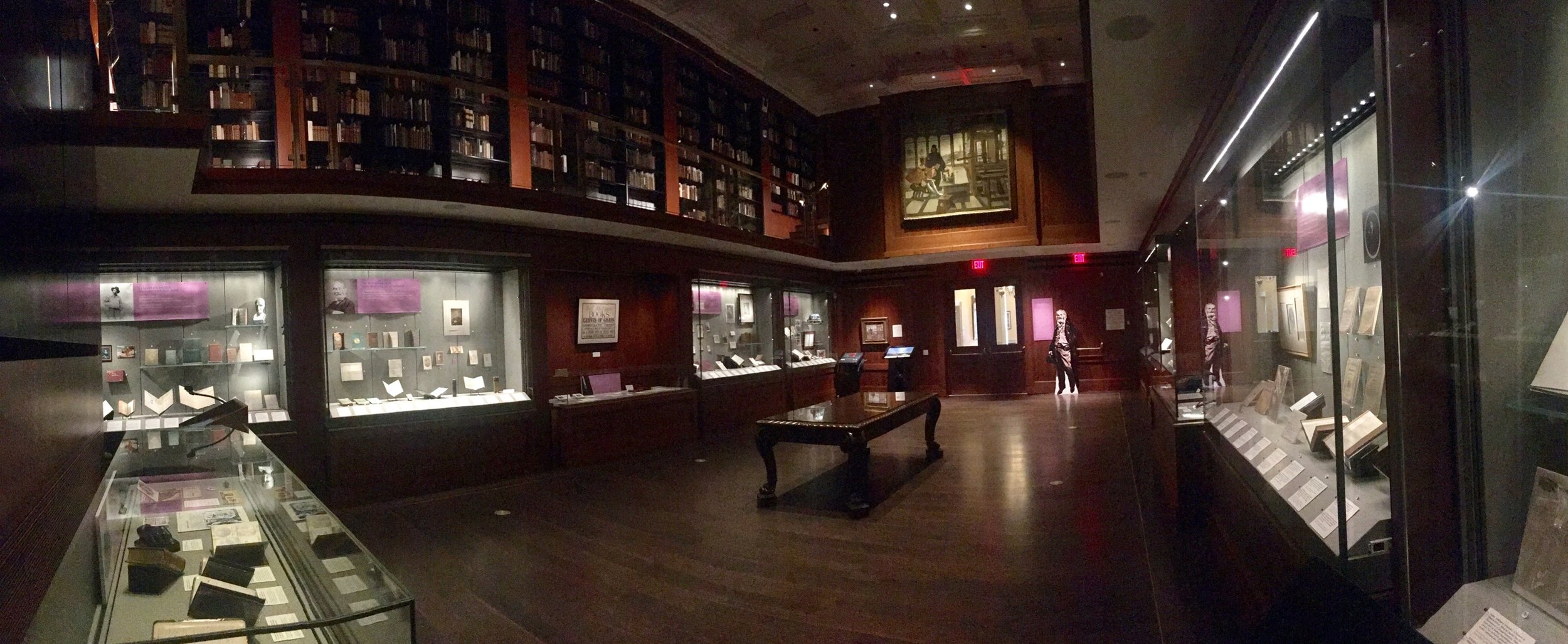

Interior of the Morgan Library in New York

If you have wandered over to the WBHB Twitter, you’ve seen my Tweets as I vagabonded about the East Coast on a research trip for most of June. I was scouting archives in between some professionalization courses looking for papers for the book Cait Coker and I have been working on the last year and a half—Women and the Book: A Bibliographic History. This is the fourth(ish) research trip that I’ve been on since I started my doctoral studies, and I approach them so differently than when I started in terms of funding, methodology, and emotional expectations about the trips.

If you’re a grad student about to go on your first trip or wondering how do you even do one of these things, here are some tips that can get you started. This is geared toward literary and historical research in institutions like libraries, historical societies, and private organizations, and I am assuming you are just getting started in your studies. Be sure to ask around your institutions as well; senior professors and librarians who do this work all the time have excellent advice to offer, and often they can link you with others to talk to on your travels. I’ll later post about archival workflow and managing all the material you are processing; this fall I’ll talk about how to use material from these trips in your pedagogy.

(I am posting pictures of libraries I have been fortunate enough to visit over the years. Because I was grad-school poor for six years, I didn’t take any other vacations. Even work trips can be restorative, so I hope the photos help brighten up not only the blog but some of your future plans.)

Planning the Trip

Radcliffe Camera at the Bodlein Library in Oxford

I started plotting research trips during my comprehensive exams, what Texas A&M calls the doctoral exams you pass before you are submitted to candidacy and get to work on your dissertation. You often need to work one to two years in advance of your project, because funding cycles can take that long to process. I applied for something in November of 2014 that I received in April of 2015 and then took up in May of 2016. This a normal scenario. More about funding below, but it is essential to think early about getting where you need to go.

How do you pick a place to visit? The biggest concern is, of course, its holdings. They need to have relevant materials for your work, and if you can make a compelling case why that institution and not just any institution, it helps a lot. Secondly is its willingness to work with graduate students, independent scholars, and/or early career scholars. If they block off funding specifically for these groups, so much the better. Third is its timeline. If you are a graduate student who teaches for their funding or are contingently employed, you cannot usually leave on a fellowship in March unless you work out something in advance with your institution (I can’t even do this, and I’m not contingent). This can be a huge headache.

Lastly, check if your institution is a member of any consortium — Folger, Newberry, English Institute. These give priorities and funding to members, and it’s worth pursuing if it is at all applicable.

Types of Funding

I have funded trips two ways—through library fellowships and by talking various sources into giving me chunks of money that I’ve strung together to stretch the funding as much as possible. I recognize throughout here I have been very fortunate and still am in having secure institutional support. But there are distinct limits on it, which I will also discuss.

Institutional Fellowships

The Folger Shakespeare Library reading room

Institutional fellowships pay you to spend time in residence, usually between two weeks to two months but sometimes up to a year. I’ve won two one-month fellowships, one from the Newberry Library and one from the University of Chicago. Both fellowship pools were reserved for graduate students and funded one month of travel to the archive. Both were in the neighborhood of $2,500. These tend to be great if you can give up a month. Some provide affordable housing, and there is usually structure of talks and coffees to keep you involved in the intellectual life of the institution. However, they are difficult for those with kids and other dependents like pets. I know several people who brought their cats with them, for example.

There are three typical kinds of funding for these fellowships: a check in advance, a check when you get there, or reimbursement. The latter two options can be a challenge, especially if you are buying plane tickets and paying for lodging up front on a graduate student budget. Inquire about policies before you accept if you know this outside of your budget.

Another thing I learned, which is perhaps obvious to some of you, is you are being paid as an employee for the fellowship. You will sign tax forms, and the withholding will probably not be taken out in advance like it typically is in a paycheck. This can put you in a pickle depending on your income and tax status. For example, say you get a $2,000 fellowship based on reimbursement. You spend $2,000 and get that back, but you will then be taxed on it as income later. You will then owe, say, $200 come tax season. That has to come out of your own pocket, because you cannot tell the institution “keep $200 for taxes.” Unfortunately, that’s not how reimbursement works. One year I won so much fellowship money I had a horrible tax season. I won’t do that again, and I hope my naivety helps you.

Professional Organizations

The grounds at Hunting Library outside Los Angeles

Professional organizations often offer research and travel funding. As an Early Modernist and book historian, the big ones for me are Renaissance Society of America, American Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies, Bibliographical Society of America, and Bibliographical Society. Some of these will be joint with institutions, and others will be standalone fellowships. I have never won one of these, but from asking around they operate more or less the same as the institutional funding option. Definitely check around for these opportunities and their deadlines.

Stringing Together Funding

You can also get creative. That’s why I affectionally my month of June vagabonding. This trip was two classes with a week in between where I did archival research. For the first class, I won a scholarship after getting turned down for a fellowship (try keeping that straight) for tuition and then and talked my institution into letting me use my $1,000 conference travel budget for the class. This meant giving up conference travel last year, which I’m fortunate to be able to do as I have secure employment; it also required reimbursement so that money was out of my account for several months. Week three was a class on textual editing that comes with a stipend through a federal grant of $1,200. The stipend is wonderful because it is not attached to expenses and let me fund a greater part of the trip.

Since both classes were on the East Coast, I squeezed in time at the Grolier Club archive and the Morgan Library; I also stayed a day and a half late to use Princeton’s archives, which is where the second class was. I was able to make most of the stipend cover my in-between week by not having to buy two cross-country plane tickets, and I made it more affordable by visiting family for several days. I was left with a deficit, $400 plus food costs, which I made up by grading exams as overtime work for my university. Being able to pick up this work is a lifesaver for me, and again not something that I know available to everyone. In summary:

Plane tickets: travel funding and stipend

Lodging: travel funding, stipend, and overtime work

Tuition: covered by stipend and scholarship

Food: overtime work

This seems lucky, but there’s an intentionality to this. I applied for those classes with those perks attached to them to make this work. I could have applied to any Rare Book School course (I currently want to take 80% of them), but by picking ones during a convenient week I was able to stretch my conference funding further. I picked this year to try to go to textual editing camp because I needed to get to the East Coast to see these papers for my book project. I do not have professional development funding to take a research trip whenever I would like, nor are there a lot of internal funding options. And since regional train tickets are much cheaper than cross-country flights, I was able to stay that extra week for very little over what it cost to fly back and forth from Los Angeles. A lot of pieces had to fall into place, but sometimes it happens!

I have also had luck extending conference travel by a few days and piggy-backing classes with research. My graduate institution was a member of the Folger consortium, which let me get funding for a monthly seminar; I then claimed that funding as a grant (which it was) and applied for grant-matching to stay an extra week and use the Folger’s materials over winter break. Another year, I was also able to use conference travel funding to get me to Europe and then won a competitive fellowship through Texas A&M to do research in England. Since plane tickets can be the most expensive part of travel, once you get to the place you are going it’s easy enough to try and stay.

The Grolier Club’s exhibition room in New York

The Application

If you are doing an institutional fellowship or one through a professional organization, you will need a compelling application. Most applications will involve a research statement or proposal, a list of materials you intend to consult, and a budget. I have also had to write a cover letter and some other paratextual documents, but these three remain pretty consistent. More than anything else, follow the application directions. You don’t know how many people don’t submit the right materials in the right order (Cait has horror stories about this). Don’t make it easy for someone to tell you no.

Research Statement

Interior of the Fisher Fine Arts Library at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia

If you are early in your studies, you may be asking: how do I pitch a project I don’t have fully formed yet? Friend, you just do. You do your best. Most research funding agencies know that you don’t fully know what you are looking for in the materials. Why else would you need to go? You just need to have a compelling reason to look. You have to be asking interesting questions. You need know why you are looking even if you’re not sure what you’ll find. You also need to know the stakes of the argument—what is on the line? Perhaps not surprisingly, my stakes tend to center on unrecovered or understudied female voices. I argue about how focusing on this gives us something that we lack. I have gotten turned down plenty*, but I’ve also gotten some acceptances.

For the research statement, the best advice is old advice: talk to people who have been successful at getting grants and have them look over your work—this is where your adviser and professors come in. Get draft feedback. Practice on people outside your field; most of the people who read these are not subject-matter experts so you need to be fluent to a general academic audience. Each application, even if it’s the same project, should be tailored to the library and its holdings. Don’t be afraid to contact the outreach coordinator at these institutions if they have one. I have had a few read my applications and give me feedback. They want the best possible projects, too. In that, we are on the same team.

*This is probably the point that I should mention, I have applied for something like a dozen fellowships or awards and gotten three. Others may have higher success rates, but in my circle this is typical. Be prepared to get told no a lot and have contingency plans.

Materials List

For the materials list, you’ll of course use the library’s catalogue and finding aid. Using each library’s catalogue can be a bit of a challenge. I will resist naming names. If there is a finding aid, be sure to reference it carefully. Because of catalogue quirks, there may be things that you are missing, and often the best way to find them is to contact the relevant curator and ask. For the love of everything, be nice to the librarians and staff while you do so (just like every line on the syllabus, I say these things because someone has not done this, not because I think it’s revelatory information). Not all catalogues are created equal, but more importantly not cataloguing practices are created equal. Places like the Folger Shakespeare Library are known for rich cataloguing, but that takes time and money that not all institutions are able to afford. Also cataloguing can be racist, sexist, ableist, colonial, and a bunch of other things that impede research or frame your expectations about the material. More practically, curators know what might be hidden in a folder marked “Correspondence” that could make your application that much stronger.

Budget

Interior of the Mansueto Library at the University of Chicago

The budget is pretty straight forward. It needs to look logical and be within the boundaries of what the fellowship expects; if the institution expects a month, budget for a month. Include things like travel, city transit passes, food, rent, and other incidentals. I have claimed things like notebooks and shampoo, which I needed while I was in town.

Interior of the Harper Memorial Library at the University of Chicago

I made my summer 2019 trip cheap, and therefore less comfortable than it might be otherwise. That’s the reality of researching on a budget. I’m writing this from the most uncomfortable dorm bedroom in the universe, but staying here for a week let me afford New York. If you can handle dorms, they are a good, affordable option. Another is airbnbs of course, as well as hostels. Ask around social media or your professional networks for house swaps for academics or leads on sublets. I won’t belabor food costs; if you are traveling on a budget you are not living excessively at home. Same rules apply. I rely on drip coffee, power bars, and sandwiches. I bought a jar of peanut butter and a half dozen apples and stashed them in the Newberry fridge for lunch. Little to no alcohol helps keep costs down (not reimbursable).

Preparing Mentally and Emotionally

The thing I never budget for, financially or intellectually, but that always comes up is my emotional needs. As you think about how long to leave and where you are going, it’s important to take yourself into account and how you will handle being separated from your space, your people, and your support networks. This takes a while to manifest, but almost everyone I know struggles with this at some point during long trips.

The longer you are separated from your routine, the more it wears you down. The biggest thing I’ve learned from my first trip in 2015 to now is to take seriously my physical health for the sake of my mental health. I keep my trip shorter or budget for my partner to visit me; this time I took a train to see my sister and 48 hours of holding a very cute niece did wonders. I started bringing a water bottle with me everywhere and filling it up to stay hydrated. I always have 2-3 protein bars in my bag. I make sure I eat at least 400 calories at every meal, because I need the fuel to stay working; somehow even just sitting there and thinking takes so much energy and it takes so much work to get into the controlled archive space that I have to remind myself to leave. I wear my Garmin watch, and it beeps when I’ve been sitting still for too long, which reminds me to take breaks and walk around the block a few times. One day I might even make it to a gym in a strange city.

Whatever taking care of yourself looks like for you, don’t ignore it. I promise it makes the trip much more productive in the long term if you are worried about getting enough done, but it’s also just a healthier experience. Research trips should be exciting and restorative, but like all good things in life you have to do some work to make that happen.

My last bit of advice is to build in time to decompress before you are wiped mentally. It is difficult to exist solely on intake mode for weeks at a time, looking through documents and having them spur thoughts that you promise you will work on later. If you are fortunate to have a month or more at an institution, think of this as a writing and brainstorming space as much as it is a space for you to work with materials. As one of my professors once told me, a fellowship is the gift of time more than anything else. If you do archival work in the mornings and write in the afternoons (or some combination) you are not wasting your time.

About the Author

Kate Ozment is assistant professor of English at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona. Currently, she is working on a book project on women’s history of bibliography. Look for her forthcoming work in Textual Cultures, Digital Humanities Quarterly, and Huntington Library Quarterly. Contact her at: keozment (at) cpp (dot) edu.

Want more Sammelband?

-

October 2022

- Oct 16, 2022 Teaching in the Maker Studio Part Two: Safety Training and Open Making

- Oct 16, 2022 Teaching Book Forms

- Oct 16, 2022 Teaching Letterpress with the Bookbeetle Press

-

September 2022

- Sep 24, 2022 Making a Scriptorium, or, Writing with Quills Part Two

- Sep 16, 2022 Teaching Cuneiform

- Sep 4, 2022 We're Back! Teaching Technologies of Writing

-

June 2020

- Jun 1, 2020 Black Lives Matter

- May 2020

-

April 2020

- Apr 1, 2020 Teaching Materiality with Virtual Instruction

- March 2020

-

February 2020

- Feb 1, 2020 Making the Syllabus Zine

-

January 2020

- Jan 1, 2020 Teaching Print History with Popular Culture

-

December 2019

- Dec 1, 2019 Teaching with Enumerative Bibliography

-

November 2019

- Nov 1, 2019 Finding Women in the Historical Record

-

October 2019

- Oct 1, 2019 Teaching in the Maker Studio

-

September 2019

- Sep 1, 2019 Graduate School: The MLS and the PhD

-

August 2019

- Aug 1, 2019 Research Trips: Workflow with Primary Documents

-

July 2019

- Jul 1, 2019 Research Trips: A Beginner's Guide

-

June 2019

- Jun 1, 2019 Building a Letterpress Reference Library

-

May 2019

- May 1, 2019 Teaching Manuscript: Writing with Quills

-

April 2019

- Apr 1, 2019 Why It Matters: Teaching Women Bibliographers

- March 2019

-

February 2019

- Feb 1, 2019 Roundup of Materials: Teaching Book History

-

January 2019

- Jan 1, 2019 Building and Displaying a Teaching Collection

-

December 2018

- Dec 1, 2018 Critical Making and Accessibility

-

November 2018

- Nov 1, 2018 Teaching Bibliographic Format

-

October 2018

- Oct 1, 2018 Teaching Book History Alongside Literary Theory

-

September 2018

- Sep 1, 2018 Teaching with Letterpress

-

August 2018

- Aug 1, 2018 Teaching Manuscript: Circulation

-

July 2018

- Jul 1, 2018 Setting Up a Print Shop

-

May 2018

- May 1, 2018 Teaching Manuscript: Commonplace Books

-

April 2018

- Apr 1, 2018 Getting a Press

-

March 2018

- Mar 1, 2018 Teaching Ephemera: Pamphlet Binding

- February 2018