Teaching Manuscript: Writing with Quills

Posted by Kate Ozment. This is the third post in a series on teaching Early Modern manuscript culture. Other posts include exercises using commonplace books and manuscript circulation. A forthcoming post on paleography will continue this series.

This semester, I am teaching a senior-level course on literature of the English Early Modern period. Students are working through three units: authorship and self-fashioning; race, gender, and modernity; and technologies of literature. This first part of this post will cover how I set up the unit on technologies of literature. The second part will be a step-by-step guide for teaching manuscript using quills.

Part One: Conceptual Framework

The goal of the unit was to meld critical making — binding pamphlets, manuscript writing, etc. — with traditional literary study to help students make arguments about materiality and textuality simultaneously. I positioned the technologies of literature unit at the end of the semester for several reasons. First, the frameworks from the first two units helped us understand more about why authors made the material choices that they did. For example, we read Bathsua Makin’s An Essay To Revive the Antient Education of Gentlewomen, in Religion, Manners, Arts & Tongues (1673) as an example of the pamphlet genre. Makin’s essay discusses class as bound up with physical bodies — that women of low class are of low “parts” and cannot reach the same standards as high-class women. She then publicizes her school at the end. The unit on authorship helped us deconstruct how Makin constructs an authoritative version of herself to reach the goal of filling her school with pupils. The unit on race, gender, and modernity gave them the language to discuss how Early Modern audiences thought about bodies, genetics, and abilities and how those ideas had become more codified by the end of the 1600s. They were then able to hypothesize why the pamphlet was the appropriate genre for Makin’s essay after they had made one.

Each unit begins with a roundtable of foundational and recent literature to introduce students to the ways Early Modernists are exploring these ideas. To prepare for this unit, all students read Richard McCabe’s “Economies of Script and Print.” Ungainefull Arte: Poetry, Patronage, and Print in the Early Modern Era, Oxford University Press, 2016, pp. 57–72. The students who were responsible for doing additional reading for a roundtable chose from the following readings:

Berek, Peter. “Genres, Early Modern Theatrical Title Pages, and the Authority of Print.” The Book of the Play: Playwrights, Stationers, and Readers in Early Modern England, edited by Marta Straznicky, University of Massachusetts Press, 2006, pp. 159–75.

McCarthy, Erin A. “Reading Women Reading Donne in Manuscript and Printed Miscellanies: A Quantitative Approach.” The Review of English Studies, vol. 69, no. 291, Sept. 2018, pp. 661–85.

Millstone, Noah. “Introduction.” Manuscript Circulation and the Invention of Politics in Early Stuart England, Cambridge University Press, 2016, pp. 1–22.

North, Marcy L. “Anonymity in Early Modern Manuscript Culture: Finding a Purposeful Convention in a Ubiquitous Condition.” Anonymity in Early Modern England: “What’s In A Name?,” edited by Janet Wright Starner and Barbara Howard Traister, Ashgate, 2011, pp. 13–42.

Smith, Helen. “'Print[ing] Your Royal Father off”: Early Modern Female Stationers and the Gendering of the British Book Trades.” Text: An Interdisciplinary Annual of Textual Studies, vol. 15, 2003, pp. 163–86.

The roundtable participants taught the rest of the class from their readings. Everyone was given a set of synthesis questions on a worksheet they that we used to guide our readings. The worksheets ensured everyone was prepared to discuss their reading from the day. By the end of class we were able to begin answering these:

What changes in technologies of literature, such as in manuscript or print, happened in the Early Modern period?

What are some norms of manuscript culture? What are some norms of print culture? What cultural weight is given to either? How do the mediums interact or how are they separate?

How might thinking about materiality or format affect how we understand and interpret the content of literature?

We usually focus on authors in literature classes, but what does thinking about how readers interacted with texts tell us? What about the lives texts lived is independent of authors?

With this background, students were prepared to link ideas of materiality in both manuscript and print to constructions of authorship, gender, and race. They were further prepared for each critical making workshop with an additional reading, detailed below. Since I am at a school without a substantial archive, I used open-access online surrogates for reading exercises. Thankfully, Early Modern culture has a lot of resources online. This is an overview of how the unit progressed, with each class representing a 50-minute class period on a MWF schedule. (I also feel bound to report that this is way more men than I taught the rest of the semester; the syllabus was gender balanced.) The class that I’ll be going into more depth with is class six.

Class One – Roundtable on Technologies of Literature

Class Two – Workshop: Pamphlet binding

Reading: Joad Raymond, “What Is a Pamphlet.” Pamphlets and Pamphleteering in Early Modern Britain, Cambridge University Press, 2003, pp. 4–27.

Class Three – Pamphlet Literary Reading

Reading: Philip Sidney, Defense of Poesy

Class Four – Pamphlet Literary Reading

Reading: John Milton, Areopagitica

Class Five – Pamphlet Literary Reading

Reading: Bathsua Makin, Essay to Revive the Ancient Education of Gentlewomen

Class Six – Workshop: Manuscript Writing

Class Seven – Workshop: Paleography

Reading: Preston, Jean F. and Laetitia Yeandle, “Introduction.” English Handwriting, 1400-1650: An Introductory Manual. Adam Matthew Publications, 1997.

Class Eight – Workshop: Paleography

Class Nine – Workshop: Manuscript Circulation

Reading: Wolfe, Heather. “Manuscripts in Early Modern England.” A Concise Companion to English Renaissance Literature, edited by Donna B. Hamilton, Blackwell Publishing, 2006, pp. 114–135.

Class Ten – Sonnets in Manuscript

Reading: Thomas Wyatt, “Whoso list to hunt” and “A renouncing love”

Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey, “The fancy wearier lover” and “Alas, so all things do hold”

Class Eleven – Sonnets in Manuscript

Reading: John Donne, “La Corona,” “The Esctacie,” “Batter my heart”

Class Twelve – Sonnets, Print, and Manuscript

Reading: Philip Sidney, Astrophil and Stella sonnets 1, 7, 52, 59

Class Thirteen – Sonnets, Print, and Manuscript

Reading: Edmund Spenser, Amoretti sonnets 1, 8, 34, 67

Class Fourteen – Sonnets, Print, and Manuscript

Reading: Katherine Philips, read prefatory material, “Upon the Double Murther of King Charles I” and “Friendship’s Mystery” in both editions and compare the prefaces and changes in the poems

Part Two: Quills and Manuscript Workshop

All materials referenced in this guide are available here at the WBHB dropbox. You can use or adapt any of these, but please provide appropriate attribution by throwing us a citation.

Materials

I purchased quills and ink from Scribal Workshop’s Etsy shop. They are a company located where I’m from in South Central Texas, and I had a good experience with them corresponding online. I have seen other shops online that sell quills, but this is the only one I have personal experience with. I want to eventually learn to cut and make my own quills, but for another day …

This is not the most inexpensive classroom exercises, but thankfully the supplies should last you for a while. I decided I needed one quill per students so they could all practice, but I had them share ink. Here is a breakdown of the cost:

Black Iron Gall Ink: $12 for a 1 oz. bottle. The bottle is about two inches tall and has a good amount of ink in it. Four students shared each bottle pretty easily, and they used less than a quarter of it in a 30-minute writing session. You can also get a larger 4 oz. bottle for $35. If you’re feeling festive, they sell other historical inks at a similar price: red, green, purple, and black walnut. You can, of course, always get calligraphy ink as well, but I’m fond of using historical re-creations when possible.

Quills: $11 for 2 quills, or $5.50 apiece. These were the most expensive part of the purchase. I bought 16 quills, so it was $176 total.

Paper: $21 for a pad of Strathmore 400 series watercolor paper at Michaels. I did not go for historical paper for this exercise mostly out of time management. I try to only add one or two new elements for each semester, and quills and ink maxed out my budget. You want good paper that holds ink for your students to practice with. You can also get mixed media paper and marker paper that is used for calligraphy.

Total cost for 16 quills, four bottles of ink, and paper: $245. Supplies that will have to be replaced next year are limited to paper, at $21.

An optional cost is learning calligraphy. Quills and dip pens are built the same way, although quills’ stiffness and quirks make it not quite translatable from pens. If you have the time and ability, a class or two in dip-pen calligraphy would help you figure out how to hold and use the quill. You can also use the wonders of you-tube and books to teach yourself, but like practicing yoga, an instructor helps a lot.

In-Class Exercises

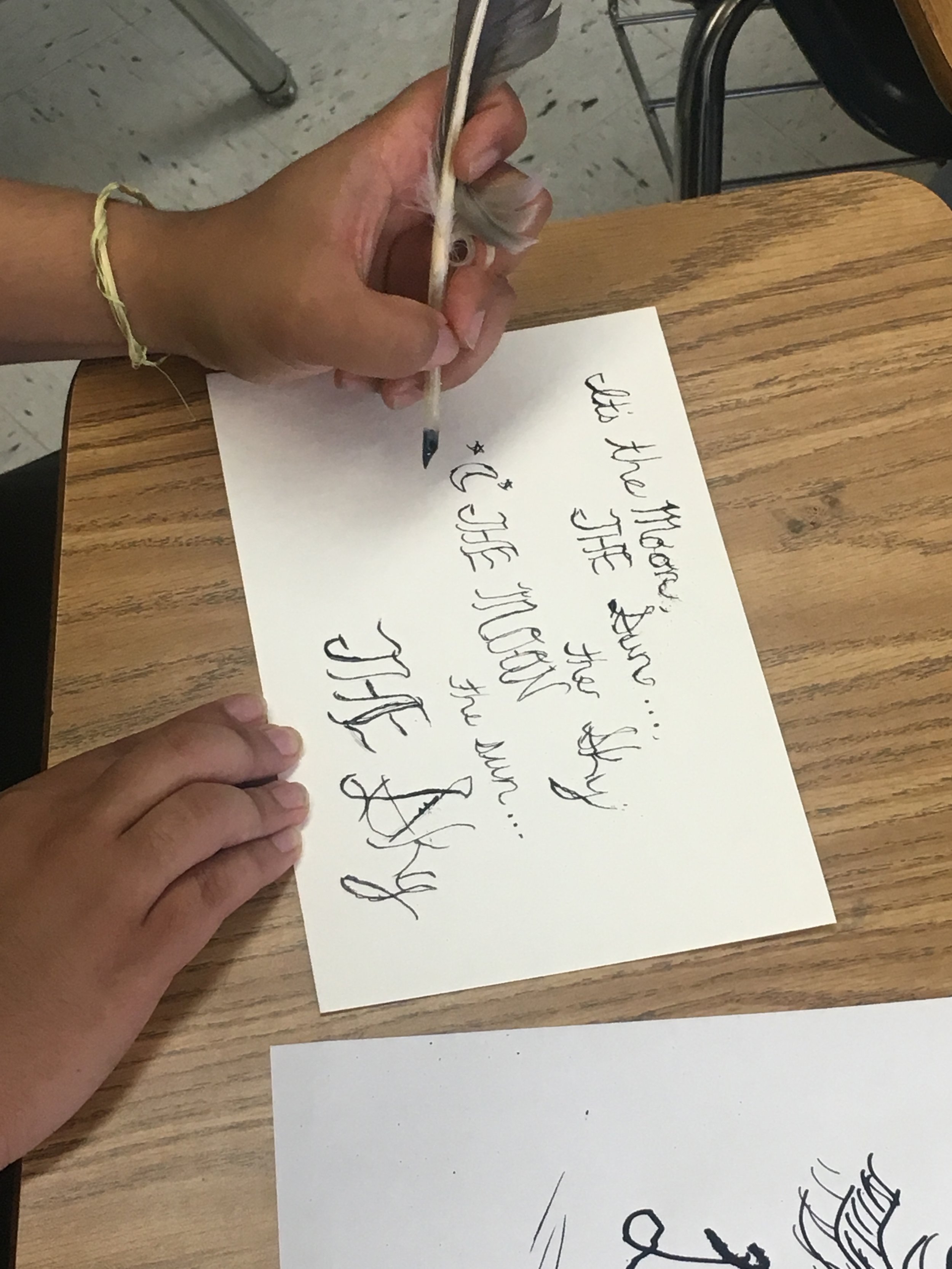

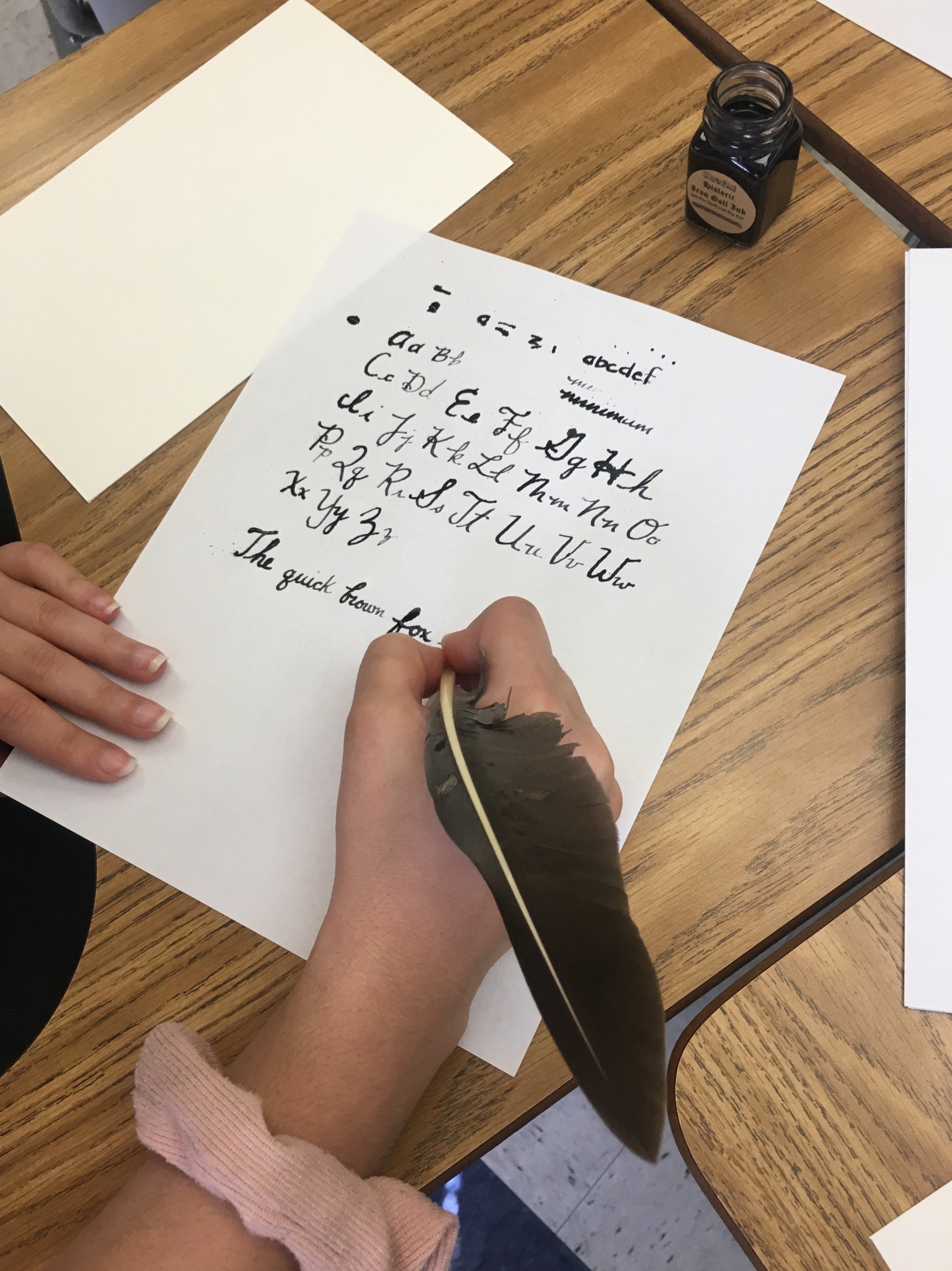

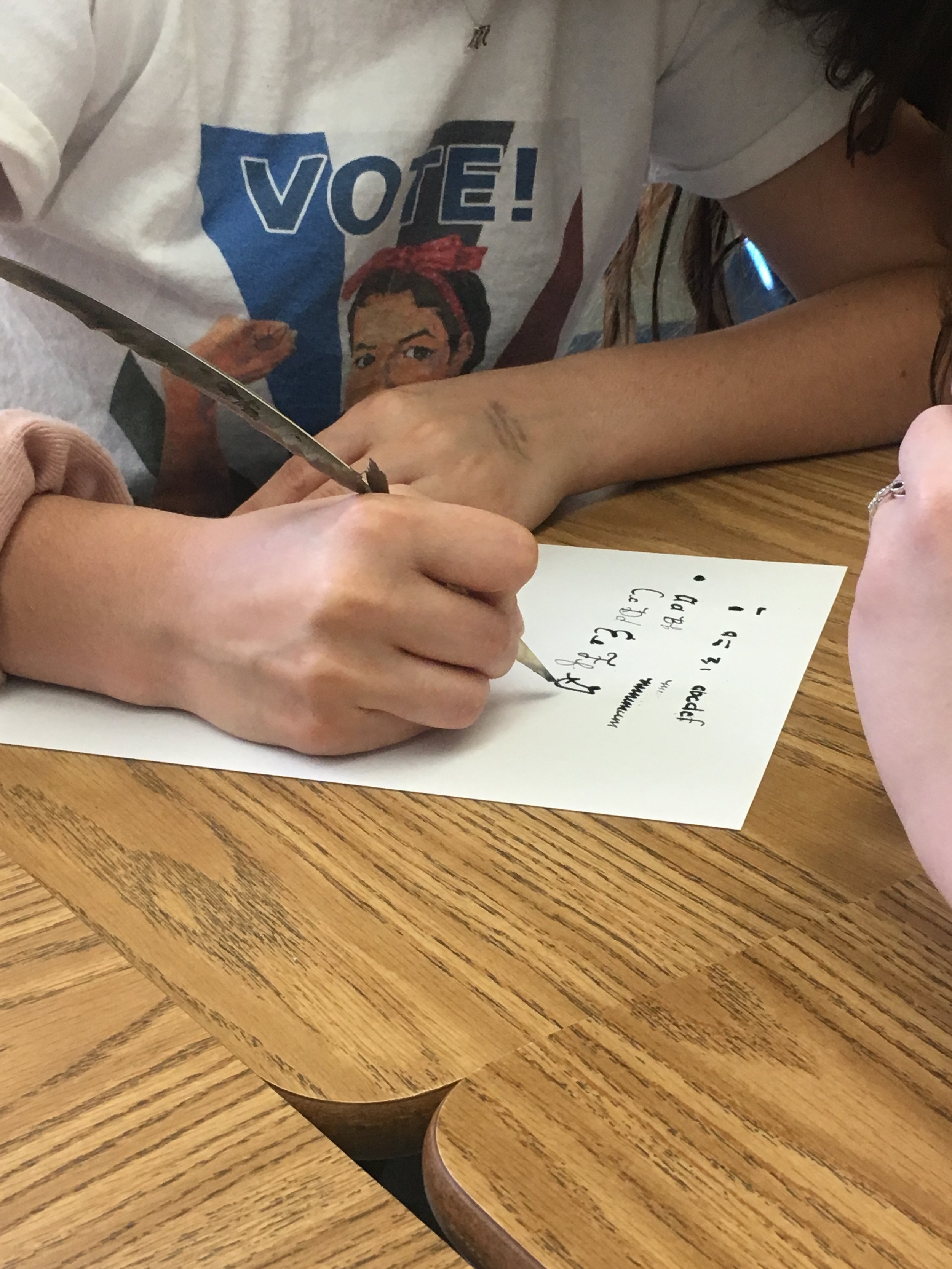

We began class by discussing different kinds of handwriting and looking at examples, all included in the PowerPoint on our Dropbox. We also watched this YouTube video about cutting and using quills so they would have an understanding of how to hold it and move their arms. Students were given small packs of printer paper — three pages or so — to practice with. They were also given a sheet of high quality paper to play with once they had gotten the hang of the quills. Here are some examples of their work:

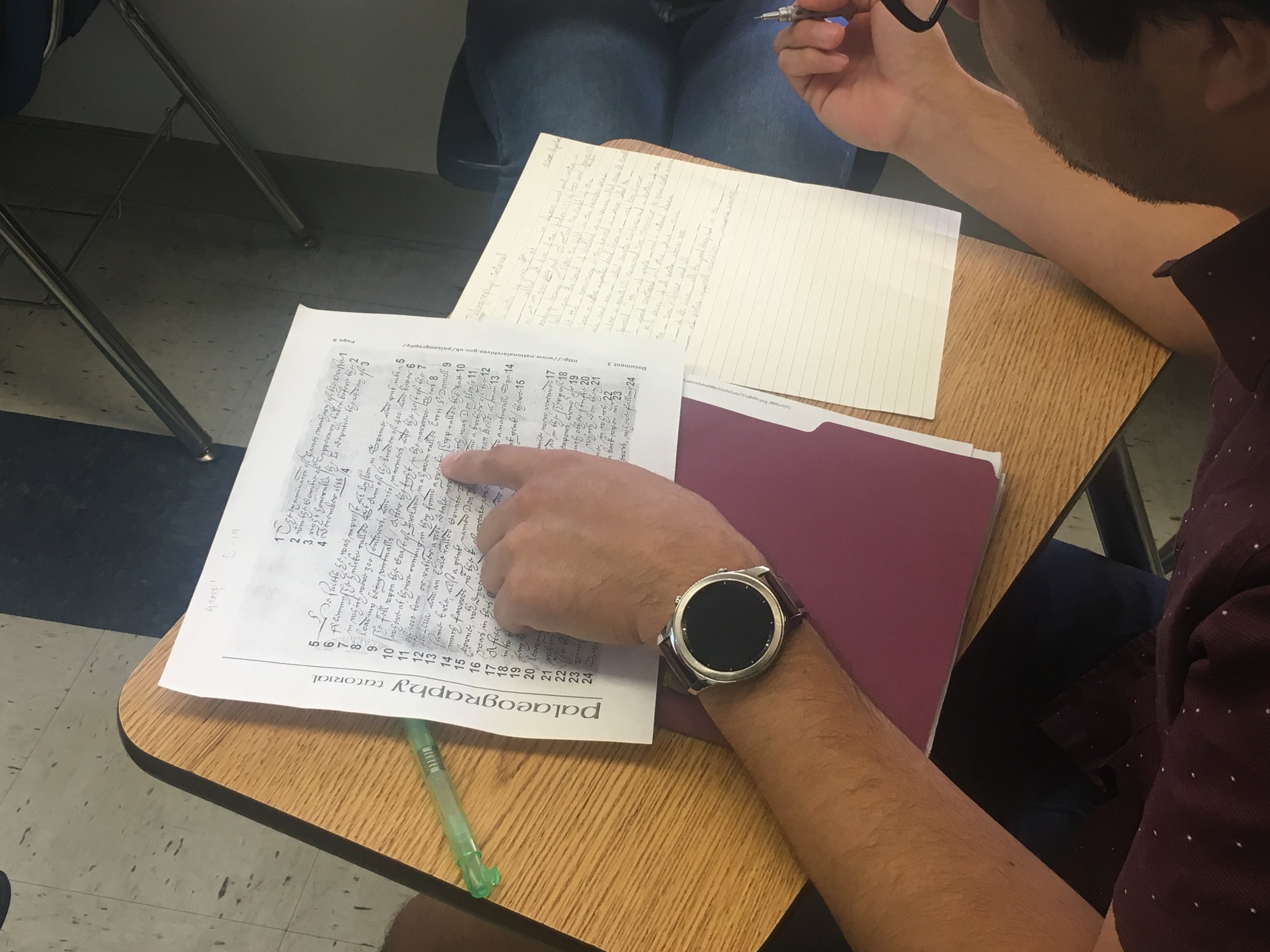

Most of this exercise was hands-off for me. The students enjoyed the work, and afterward they were better able to decipher Early Modern secretary hand (pictured in the last photo above). They also learned how to adapt their style to the tools at hand. Those who had done calligraphy before adapted more quickly. Ink splotches got less and less frequent. Someone even wrote a letter to a friend.

While there are distinct learning outcomes, listed below, for this project, a big impulse was just to have fun. There’s a pedagogical value in the excitement of getting to write with a quill that I try not to intellectualize. Critical making is fun and it makes people excited about coming to class. I love that.

To connect this to learning outcomes, I had them practice this before doing paleography (the subject of an upcoming post). When we began to then work on reading secretary hand, students began bringing up things they had learned from using quills themselves—oh they must have run out of ink here, or this is obscured by a blot, that happened to me, too. It better connected them with the digital surrogates we were using since I can’t take them into an archive and show them samples of manuscripts. But now, they had done this. They knew how much of a skill it was and how the tools shaped what kind of writing they were reading. Just like going to the Globe can unlock how Shakespeare thought about space and framing, quills make visible the mechanisms through which people wrote and thought about writing.

About the Author

Kate Ozment is assistant professor of English at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona. Currently, she is working on a book project on women’s bibliographic history. Contact her at: keozment (at) cpp (dot) edu.

Want more Sammelband?

-

October 2022

- Oct 16, 2022 Teaching in the Maker Studio Part Two: Safety Training and Open Making Oct 16, 2022

- Oct 16, 2022 Teaching Book Forms Oct 16, 2022

- Oct 16, 2022 Teaching Letterpress with the Bookbeetle Press Oct 16, 2022

-

September 2022

- Sep 24, 2022 Making a Scriptorium, or, Writing with Quills Part Two Sep 24, 2022

- Sep 16, 2022 Teaching Cuneiform Sep 16, 2022

- Sep 4, 2022 We're Back! Teaching Technologies of Writing Sep 4, 2022

-

June 2020

- Jun 1, 2020 Black Lives Matter Jun 1, 2020

-

May 2020

- May 1, 2020 The Special Collections Classroom in the Time of Covid-19 May 1, 2020

-

April 2020

- Apr 1, 2020 Teaching Materiality with Virtual Instruction Apr 1, 2020

-

March 2020

- Mar 1, 2020 Teaching Manuscript: Lessons Learned From Quill-Cutting Mar 1, 2020

-

February 2020

- Feb 1, 2020 Making the Syllabus Zine Feb 1, 2020

-

January 2020

- Jan 1, 2020 Teaching Print History with Popular Culture Jan 1, 2020

-

December 2019

- Dec 1, 2019 Teaching with Enumerative Bibliography Dec 1, 2019

-

November 2019

- Nov 1, 2019 Finding Women in the Historical Record Nov 1, 2019

-

October 2019

- Oct 1, 2019 Teaching in the Maker Studio Oct 1, 2019

-

September 2019

- Sep 1, 2019 Graduate School: The MLS and the PhD Sep 1, 2019

-

August 2019

- Aug 1, 2019 Research Trips: Workflow with Primary Documents Aug 1, 2019

-

July 2019

- Jul 1, 2019 Research Trips: A Beginner's Guide Jul 1, 2019

-

June 2019

- Jun 1, 2019 Building a Letterpress Reference Library Jun 1, 2019

-

May 2019

- May 1, 2019 Teaching Manuscript: Writing with Quills May 1, 2019

-

April 2019

- Apr 1, 2019 Why It Matters: Teaching Women Bibliographers Apr 1, 2019

-

March 2019

- Mar 1, 2019 What does it mean to teach a feminist book history? Mar 1, 2019

-

February 2019

- Feb 1, 2019 Roundup of Materials: Teaching Book History Feb 1, 2019

-

January 2019

- Jan 1, 2019 Building and Displaying a Teaching Collection Jan 1, 2019

-

December 2018

- Dec 1, 2018 Critical Making and Accessibility Dec 1, 2018

-

November 2018

- Nov 1, 2018 Teaching Bibliographic Format Nov 1, 2018

-

October 2018

- Oct 1, 2018 Teaching Book History Alongside Literary Theory Oct 1, 2018

-

September 2018

- Sep 1, 2018 Teaching with Letterpress Sep 1, 2018

-

August 2018

- Aug 1, 2018 Teaching Manuscript: Circulation Aug 1, 2018

-

July 2018

- Jul 1, 2018 Setting Up a Print Shop Jul 1, 2018

-

May 2018

- May 1, 2018 Teaching Manuscript: Commonplace Books May 1, 2018

-

April 2018

- Apr 1, 2018 Getting a Press Apr 1, 2018

-

March 2018

- Mar 1, 2018 Teaching Ephemera: Pamphlet Binding Mar 1, 2018

-

February 2018

- Feb 1, 2018 Empirical Bibliography: What It Is and Why It Matters Feb 1, 2018

- Feb 1, 2018 Introducing Sammelband: A Book History Pedagogy Blog Feb 1, 2018