Teaching Manuscript: Circulation

Posted by Kate Ozment

In addition to having my eighteenth-century students do commonplace books, I also asked them to engage with a more collaborative exercise in manuscript culture: circulation. We covered coteries in class, discussing how authors like Katherine Philips, John Dryden, and John Wilmot, Earl of Rochester would have published their manuscripts via social circles and copies instead of through print. My students (or perhaps modern students) tend to instinctively understand coterie culture because most of them actively curate online platforms aimed at different groups. In class, we discussed how they differentiate what they post on Instagram, Snapchat, Facebook, Twitter, GroupMe threads, YouTube, etc. etc. (Apparently Facebook is for old people now, by the way. Also they're all watching reruns of One Tree Hill, Gilmore Girls, and Friends, which are not for old people. This is my update on the youth).

For example, their course's GroupMe thread was the most reserved communications, as they recognized it as a somewhat professional environment. They also all differentiated between their fully public accounts, the ones their older family members and parents are on, and ones that are fully for their friends. They know, as many people have learned, that posting to public accounts can attract abusive behavior from trolls and bots, so they only post very certain things there if at all. They also post very different things for their friends than their parents. This naturally let us talk about print versus manuscript and the dangers of one kind of publication over another. Just as certain groups online—women, POC, and queer-identifying folks—are more vulnerable to the vitriol of angry Twitter users, so too was Aphra Behn more open to criticism than John Dryden. We decided that the apparent embarrassment that Philips felt when her poems were published in an unauthorized form was what they might feel if their parents got to see all their Snapchat posts only meant for friends.

All of that is to say—they took to this very easily and had a lot of fun with it. They generously let me keep the artifacts of their exercise, which I'll post below.

In-Class Manuscript Circulation

This exercise should take about 30 minutes of class time, but you are absolutely able to adjust it longer or shorter depending on your classes. I had about 30 students enrolled at this point in the semester, and most were present. These are the materials you will need:

Manuscript exercise prompt (1 per student) – cost is that of paper

Base text for copying (1 per group) – cost is that of paper

Optional: feathers with colored yarn tied around them – cost is about $12 plus yarn scraps

Students will each need a single piece of paper and a pen

The prompt, PowerPoint (and in a PDF), and the base text that I used are all posted here on our WBHB dropbox: https://www.dropbox.com/sh/tlkg0lzywwsaixf/AADheTsG2TqmGDNOgHniYXQWa?dl=0

In my dreams, I bought turkey feathers and expertly showed them how to cut a quill. Logistically and practically, I don't think that's something I'll be able to do with 30 students. But I wanted to capture the feel of manuscript a bit, so to divide students into groups I used pigeon feathers. There are plenty of non-animal options as well, but these were inexpensive and visually appealing, so that's what I went with. I tied colored strings around each one, and then put them in a cup and had students pick groups based on what color they received. You could do this exercise without this, but I thought it added a bit of whimsy. Students kept the feathers.

Five groups of pigeon feathers tied with colorful yarn in maroon, pink, yellow, gray, and blue.

They had a prompt with detailed instructions, and I had slides on a PowerPoint that showed them what step we were in (see the link above for these). Once they were in groups, I went over the general trajectory of what we were doing, which is as follows:

One person per group would get a copy of a paragraph. Others were not allowed to look or collaborate so this was done somewhat in "secret" for reasons that will become clear. That person would copy the text onto a new sheet of paper, then return the original printed sheet to me. I have a slide about acceptable, likely, and encouraged alterations. A sense of humor is encouraged.

The first person passes their handwritten sheet to the next person in the group, who makes a new copy. The second person then returns the first copy to its owner, before passing their new one onto the third person. This continued until everyone was sitting with their own handwritten copy on their desk. I had all the "originals" that were typed.

Everyone added their copy into a pile and mixed them up, then read them aloud and shared as a group. They talked about the alterations and, in most cases, laughed at some of the crazy things their classmates had done.

At this point, we came back as a class and discussed the process. We talked about what changes they made and why, and then talked about how approximate we think this might be to eighteenth-century manuscript practices. I took one piece out of the progression of one group and asked them to think about how much of the story is missing if this single piece is the only that survives, or the only that gets archived, or the only that is referenced when someone makes a critical edition. Then we talked about authorship. Who is the author of this single piece if it's based on something else someone wrote? How would one make a critical edition or a single authoritative text you could read based on all of their different copies? To whom would that critical edition be attributed?

Lastly, because we had extra time, we played researcher. I collected each group's papers and mixed them up, then handed them to another group. The groups then tried to figure out in what order they were written based on changes in the text. In the future, I might even have them edit and annotate these.

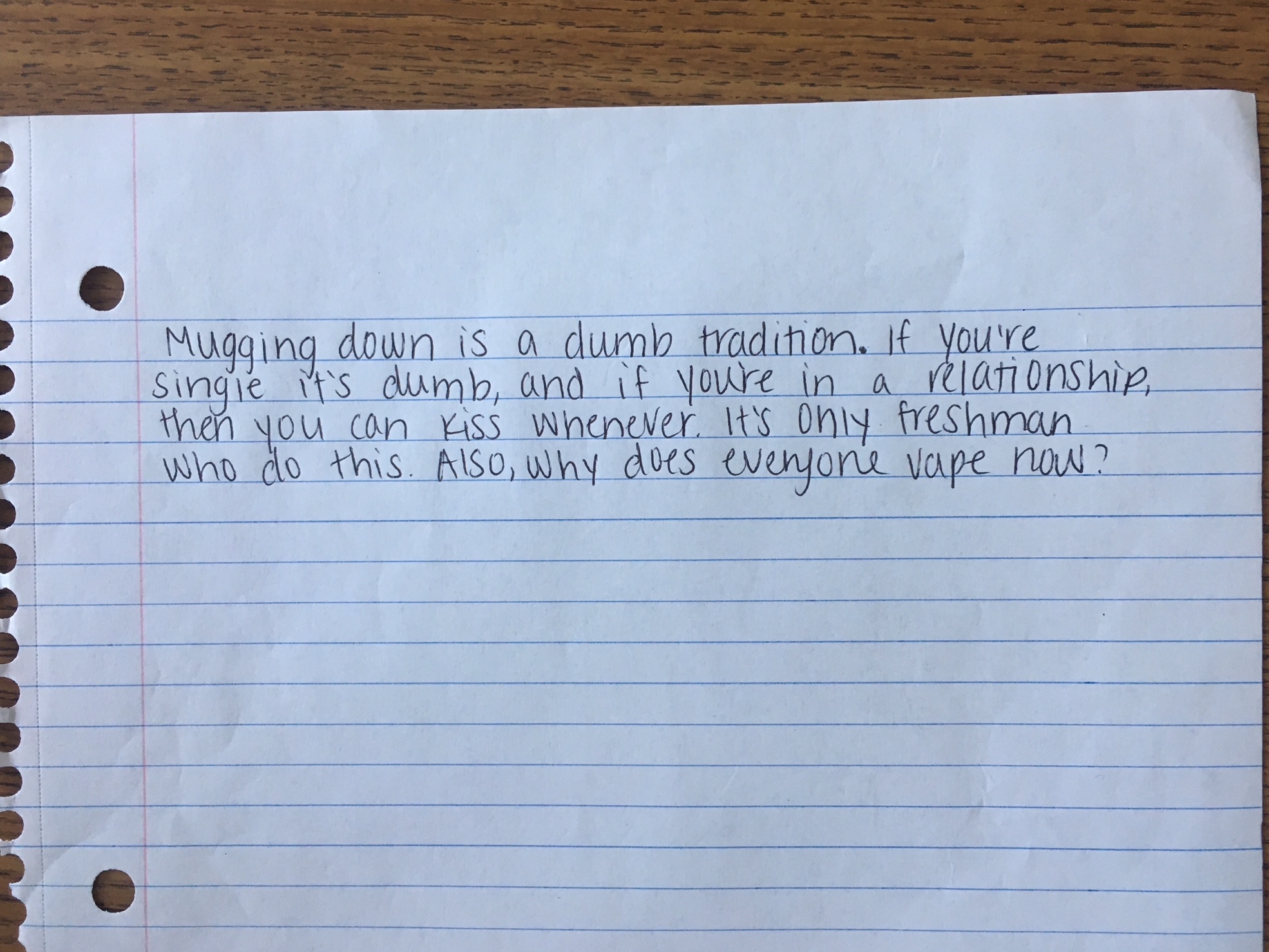

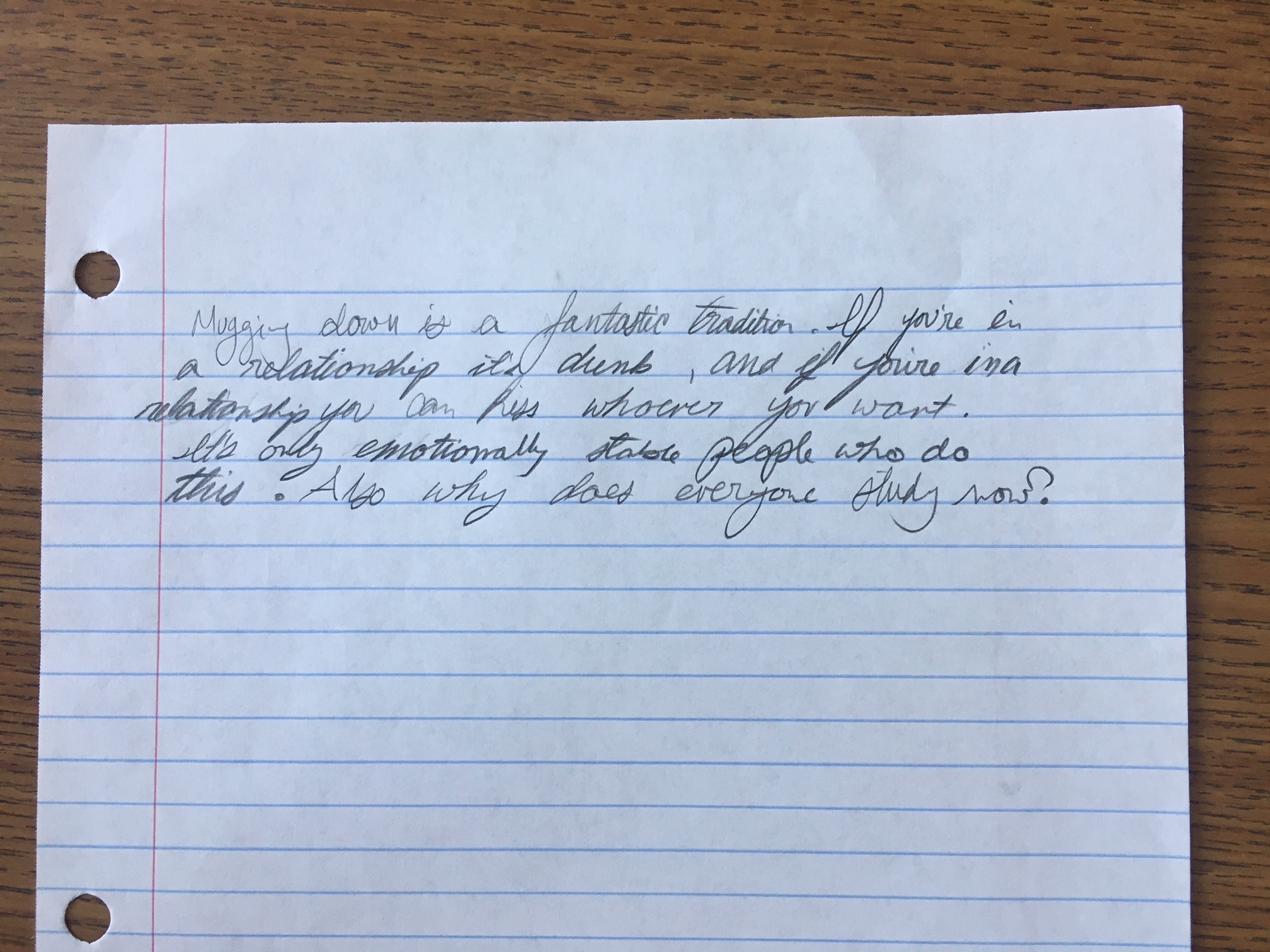

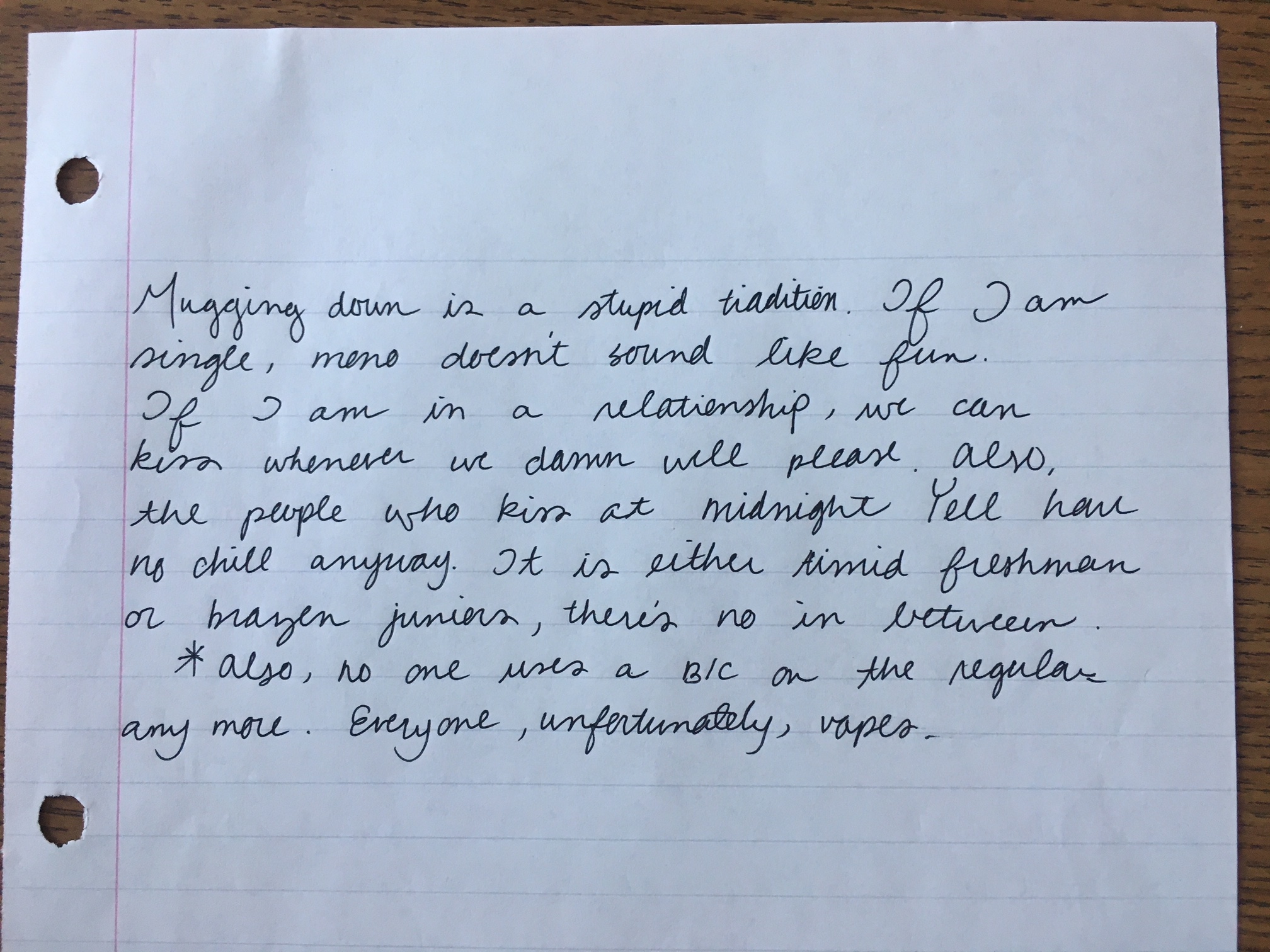

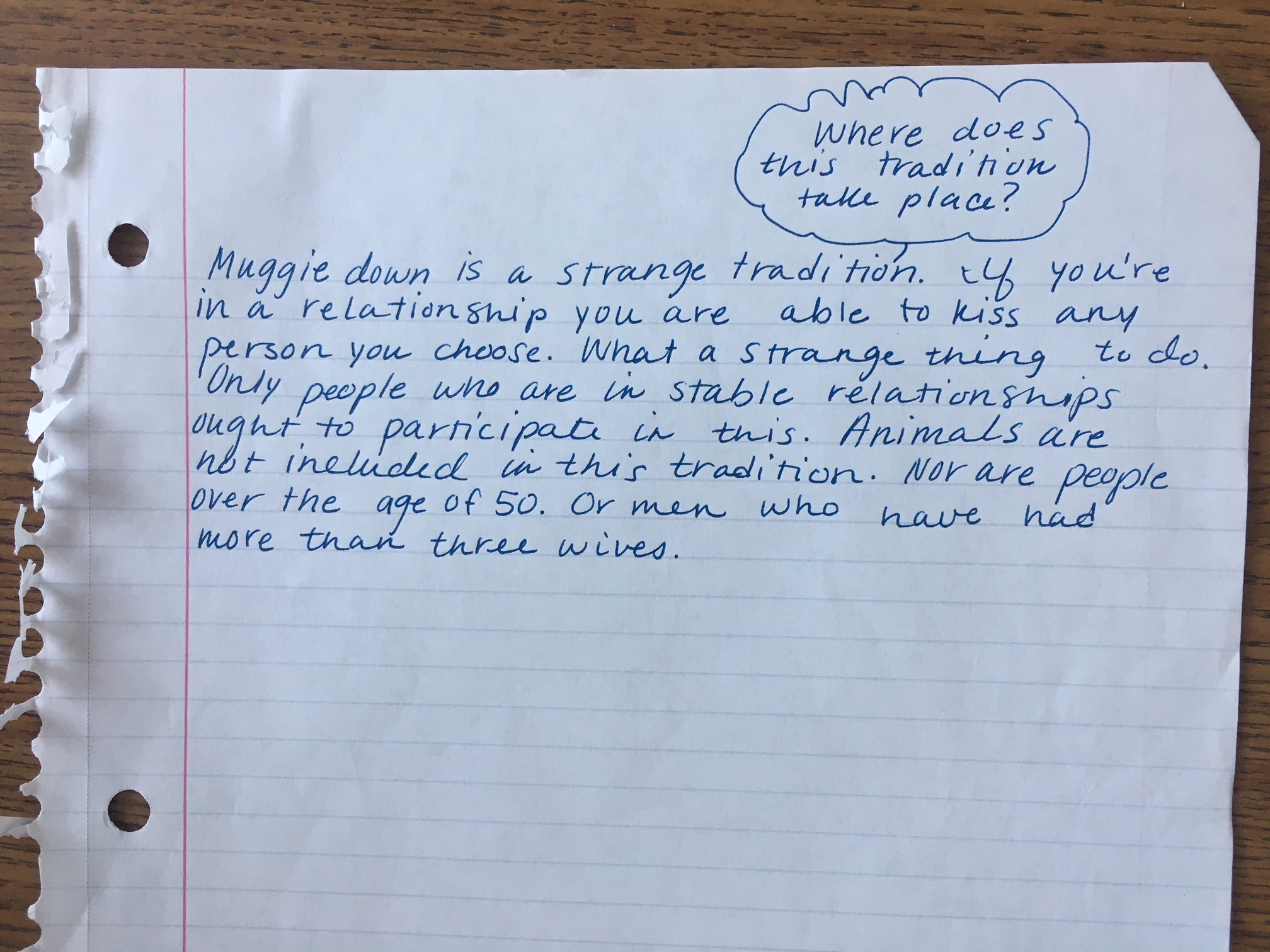

Here's an example of what they produced. The original copy text is below, and their handwritten responses are included in images. If the text seems a bit strange, all I can say is that Texas A&M is its own place with some very strange traditions. I have not parsed out in what order they were written yet.

Original text: Mugging down is a stupid tradition. If I am single, mono doesn’t sound like fun. If I am in a relationship, we can kiss whenever we damn well please. Also, the people who kiss at Midnight Yell have no chill anyway. It is either timid freshman or brazen juniors, there’s no in between.

Reflections

Overall, this exercise went the best of the ones I tried this semester, and it was by far the cheapest. I did not anticipate that they would take so easily to manuscript culture in the digital age, but as I indicated at the beginning, I think this group understands selective publication very intimately. I think what this offered the most, which I had not guessed, was the conversation about authorship, editing, and archives. I could of course explain all that to them, but doing it and seeing how authorship is a messy process, how the text is an unstable format, let us talk about this so intimately. We had hard documents to hold up and talk about. They were the authors, who in some case were wrangling with their own ownership versus what they understood about critical editions. It was fascinating, and the best 15 minutes of class I had all semester. There are applications for this that I will probably use in book history–focused classes or textual studies classes, maybe even having them mark up the texts with TEI and make an edition of their work. There are a lot of possibilities, so please share yours if you try this!

About the Author

Kate Ozment is assistant professor of English at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona. Her current projects include Eliza Haywood's pamphlet shop and a book project theorizing feminist bibliography with her WBHB co-editor, Cait Coker. Contact her at: kateozment (at) gmail (dot) com.

Want more Sammelband?

-

October 2022

- Oct 16, 2022 Teaching in the Maker Studio Part Two: Safety Training and Open Making

- Oct 16, 2022 Teaching Book Forms

- Oct 16, 2022 Teaching Letterpress with the Bookbeetle Press

-

September 2022

- Sep 24, 2022 Making a Scriptorium, or, Writing with Quills Part Two

- Sep 16, 2022 Teaching Cuneiform

- Sep 4, 2022 We're Back! Teaching Technologies of Writing

-

June 2020

- Jun 1, 2020 Black Lives Matter

- May 2020

-

April 2020

- Apr 1, 2020 Teaching Materiality with Virtual Instruction

- March 2020

-

February 2020

- Feb 1, 2020 Making the Syllabus Zine

-

January 2020

- Jan 1, 2020 Teaching Print History with Popular Culture

-

December 2019

- Dec 1, 2019 Teaching with Enumerative Bibliography

-

November 2019

- Nov 1, 2019 Finding Women in the Historical Record

-

October 2019

- Oct 1, 2019 Teaching in the Maker Studio

-

September 2019

- Sep 1, 2019 Graduate School: The MLS and the PhD

-

August 2019

- Aug 1, 2019 Research Trips: Workflow with Primary Documents

-

July 2019

- Jul 1, 2019 Research Trips: A Beginner's Guide

-

June 2019

- Jun 1, 2019 Building a Letterpress Reference Library

-

May 2019

- May 1, 2019 Teaching Manuscript: Writing with Quills

-

April 2019

- Apr 1, 2019 Why It Matters: Teaching Women Bibliographers

- March 2019

-

February 2019

- Feb 1, 2019 Roundup of Materials: Teaching Book History

-

January 2019

- Jan 1, 2019 Building and Displaying a Teaching Collection

-

December 2018

- Dec 1, 2018 Critical Making and Accessibility

-

November 2018

- Nov 1, 2018 Teaching Bibliographic Format

-

October 2018

- Oct 1, 2018 Teaching Book History Alongside Literary Theory

-

September 2018

- Sep 1, 2018 Teaching with Letterpress

-

August 2018

- Aug 1, 2018 Teaching Manuscript: Circulation

-

July 2018

- Jul 1, 2018 Setting Up a Print Shop

-

May 2018

- May 1, 2018 Teaching Manuscript: Commonplace Books

-

April 2018

- Apr 1, 2018 Getting a Press

-

March 2018

- Mar 1, 2018 Teaching Ephemera: Pamphlet Binding

- February 2018