Why It Matters: Teaching Women Bibliographers

Posted by Kate Ozment; special thanks this month to Cait Coker, Madeline Keyser, and Kandice Sharren for providing feedback on a draft in progress.

For Women’s History Month 2019, we wrote and posted thirty-one daily profiles on women who worked within bibliography broadly defined, ranging from the nuns of San Jacopo di Ripoli in the fifteenth century to the Off Our Backs feminist-run periodical which ended in 2008. We used the hashtag #31daysofwomensbookhistory to create a searchable collection, and the profiles were posted on our Twitter and Facebook accounts. Based on a quick Twitter poll, we focused this year on historical printers, librarians, cataloguers, and archivists.

These profiles all grew out of another query, where we asked the SHARP-L listserv (Society for the History of Authorship, Reading and Publishing) and our social media networks for examples of women working in bibliography. We compiled all the answers in this spreadsheet, and most of the Women’s History Month profiles were selected from this larger list. The institutional knowledge offered by those who shared examples has been invaluable for our research and teaching because it has shown us the ways that studies of the book has drawn its disciplinary boundaries, and consequently the ways that I as a scholar of the book in the twenty-first century have inherited those divides.

This is a common issue with women’s work more broadly, and I see it often in the women’s writing that I teach as a literature professor. Recently, my graduate class on the global eighteenth century encountered documentary traces of Native American women’s lives in the (personally recommended) anthology Early Native Literacies edited by Kristina Bross and Hilary E. Wyss. These documents were testimonies taken in the infanticide case, and in her commentary Ann Marie Plane writes about how we define what is “women’s writing” can work to devalue certain kinds of histories:

It is arguable that these documents are out of place in a collection that focuses on Native literacy. After all, other than the mark (a vertical line) that Sambo placed, in lieu of a signature, on a bond for her appearance, none of these women can be said to have written a word—not here and, as far as we know, not at any time in their lives. That, however, is precisely the dilemma that faces scholars who are interested in women’s writing in general and Native American women’s writing in particular. Of the few documents that reveal aspects of women’s lives in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, all but a handful were written by men. Of the documents that speak to the experiences of Native American women—certainly among the records I combed for a larger study of Native American marriage in southeastern New England during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries—not one was actually penned by a Native American woman. Thus, although purists may wish to adhere to a strict definition of “women’s writing,” doing so both elides and erases women in general and Native women in particular from the pages of history. (88)

Native American women’s writing has its own set of particular circumstances that are not the duty of this post to unpack (but can certainly be explored in that anthology and Decolonizing Methodologies by Linda Tuhiwai Smith). But the disciplinary and material definitions that Plane characterizes are similar to the distinctions that I have seen made by scholars in the areas I am researching for our book project: Early Modern women’s writing, African-American print culture in the nineteenth century, and queer zine cultures of the late twentieth century. How we think about and define keywords matters, and often definitions created from a narrow set of lived experiences and material objects can work to erase those who do not “fit.” This is the experience of many of the women bibliographers included in our profiles.

This is not to say that we have, superwoman-like, plucked these women from obscurity. On the contrary, many of these women are justifiably well known within their circles. Lillian H. Smith has a branch of the Toronto Public Library named after her; Smith College Special Collections has named its rare book room for its longtime curator Ruth Mortimer; Katherine F. Pantzer and Marie Tremaine are honored with named fellowships from the bibliographical societies of America and Canada, respectively; those who study women in libraries have probably heard of Dorothy B. Porter or Henriette Avram; several of the women printers we highlighted like Charlotte Guillard and Anaïs Nin have whole books about them. And it is not surprising to us at all that much of our information about women librarians is coming from other women librarians, blogging about their institutions and personal research.

Instead, for me as a scholar who is reassessing what it is exactly that I do and how can I define it in a way that is useful and flexible enough to encompass a broader range of texts and experiences, learning this information that just so happens to be about women and just so happens to be generally left out of studies of the book has brought up several suggestions that I am exploring. Our profiles were biographical; they focused largely on people with a few presses thrown in. But to teach feminist bibliography is to teach these subjects’ work as contributions to a larger conversation (and there is something to be questioned about whether or not we needed biography as a starting point or why was my impulse to go there to begin with). Here are two lessons I have learned from these women and their work:

First, there are the norms of modern academia, which value articles, monographs, and peer-reviewed published texts. But by focusing on certain kinds of scholarly output and activities as more important than others, we have missed a rich history of women’s labor that can and should dramatically reshape the way we conceptualize the history of the book. Other labor also matters: the teaching of librarians and archivists; the training of future bibliographers; the building of card catalogues; the creation of infrastructure like MARC; the building of special collections and the collecting of books and archival materials, especially for under-represented genres and populations. More than one obituary discussed someone’s teaching as a distraction from her publishing, and while it is harder to “assign” someone’s career in a class like one would an article, we should absolutely recognize that training an entire generation of librarians and bibliographers is valuable work.

Secondly, when we look to the not-so-distant past when women could not go to the same universities or training programs or for various gatekeeping reasons didn’t publish articles, it becomes clear that we must redefine what is valuable or we will lose these women’s contributions. Similarly to Plane’s point about Native American women’s writing, being bibliographical purists works to erase women and other minority bibliographers from our field. Wonderful work has been done on these subjects, and bringing them explicitly into the history of bibliography will only strengthen our understanding of books as material objects with cultural significance. Without them, we impoverish our discipline.

This experience has allowed me to articulate a few paradigms that I am going to adopt as I move forward with my teaching of books as material objects. These are of course informed (as is everything I do) by my training as a literature scholar who is still learning how much there is to learn about the interdisciplinary work of studies in the book:

Teach about the interpretive aspects of analytical and descriptive bibliography; discuss how no person is capable of complete objectivity and instead we should be critical and transparent about the beliefs, values, and goals we bring to the analysis of a book or other object or text.

Teach about the function and structure of archives and special collections alongside how to read the rare books, manuscripts, and materials we use from them; in particular, students should understand how cataloguing functions, the structures that cataloguers and preservationists work within, and the subjective and interpretive choices cataloguers can make.

Teach about the theory of the archive and special collections as both spaces and historical desires; students should understand that archives are political spaces like any other and be introduced to the concepts of queering and decolonizing the archive; in particular discuss how archives are colonial and imperial constructions that can put problematic interpretive frameworks on texts and histories.

Teach canon-building, but not just as a literary history or narrative; teach how book collecting and sales influence value and prestige and how institutions’ missions and goals can affect what sorts of material are collected; teach about how building collections around marginalized or under-represented topics is an act of interpretive scholarship itself that can also dramatically change the work other scholars do.

It is true that this class will look dramatically different than any book history class I have ever taken. But it is also true that these are some of the first steps toward training bibliographers and book historians who have the theoretical tools and frameworks to read material books within the context of their production and the context of our current moment. As feminist book historians, we need to be doing both.

About the Author

Kate Ozment is assistant professor of English at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona. Currently, she is working on a book project titled Women and the Book that theorizes feminist bibliography with her WBHB co-editor, Cait Coker. Contact her at: keozment (at) cpp (dot) edu.

Women’s History Month Profiles

Written by Cait Coker and Ozment

March 1

Today's profile is on Night Heron Press. Night Heron Press was a publishing house founded in 1982 that focused on lesbian women's experiences in the American South. Julie R. Enszer writes that this movement "enabled women to imagine and implement cultural projects that expressed the movement’s values." Night Heron Press published chapbooks, cheap stab-sewn pamphlets. The founders, Minnie Bruce Pratt, Cris South, and Mab Segrest, wrote in a grant application that their intention was "to publish the work of Lesbian women, living in or linked to the South in some way who have been denied access to more traditional means of publication because of their sexuality, race, class, ethnicity, or political point of view." Night Heron was one of the several collectives that arose to combat the invisibility of southern lesbian literary culture. We have a pile of articles at the WBHB on lesbian print culture, and Night Heron is one of the many examples of how cheap printing like chapbooks (similar to Early Modern pamphlets and modern zines) allowed communities of women writers to self-fashion an identity of their own.

March 2

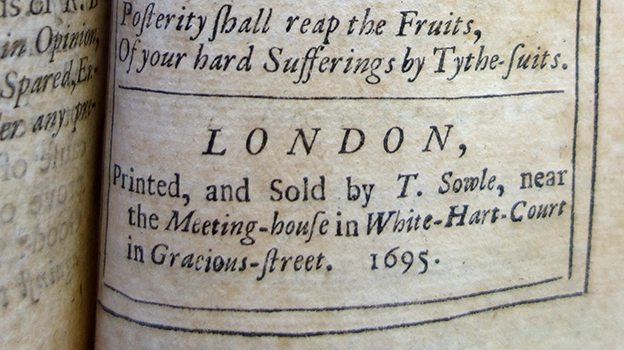

Today's profile is Tace Sowle-Raylton, Quaker publisher in 17th century England. Sowle-Raylton was a printer and a bookseller who was a revolutionizing force in the Quaker community. Louisiane Ferlier writes that she "adopted modern commercial techniques, a professionalization visible through the collections of the depository library." Like many women in the trades, Sowle-Raylton took over the business from her father and ran it full time sans male control from at least 1691 forward. She was praised at the time for her business acumen and technical skills. Sowle-Raylton continues to be a valued force for the development of early Quaker literary culture. Her family included a sister who married into the family of the first Quaker printer in America, bringing her skills with her and fostering important cultural changes in America.

March 3

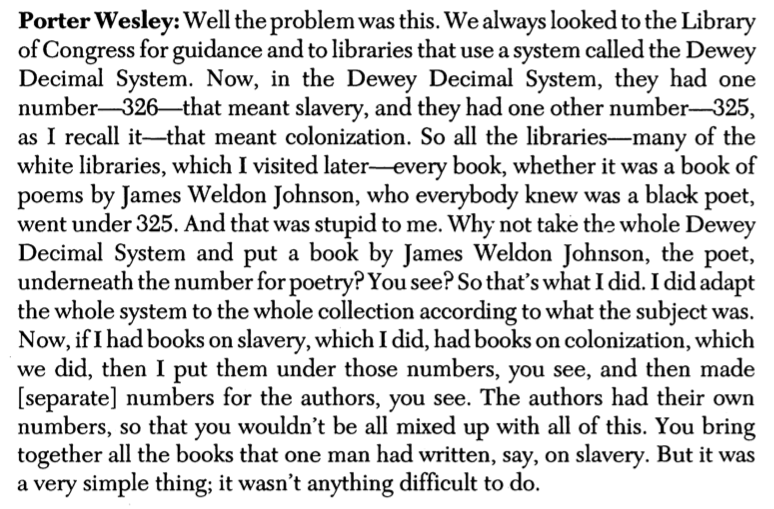

Today's profile is Dorothy B. Porter, who was a librarian, cataloguer, bibliographer, curator... well just about everything at Howard University. Porter was responsible for turning Howard into a world-class research center for black literature and culture. She's a bibliographer after our own hearts, because she completed some of the earliest foundational work in Af-Am literary studies. Porter gave an oral history in which she describes combating the Euro-centricism in the Dewey decimal system where all black writing was marked as colonization or slavery. We have included an excerpt of how she worked against these structures and changed them to better reflect her material (we have the whole oral history; if you're interested, contact us).

Porter's work has gotten justifiable attention lately (Smithsonian piece and Laura Helton's PMLA piece that just came out), and she bucks the trend of women's work being undervalued (three gigantic cheers for more of that, please!). Sometimes it takes someone truly remarkable to break through. And Porter was. She turned 3,000 items into hundreds of thousands. She wrote one of the first anthologies of African-American voices from her work in the archives. She made bibliographies. She pioneered appraisals for black literature. She did it all. And her work will justifiably impact generations.

March 4

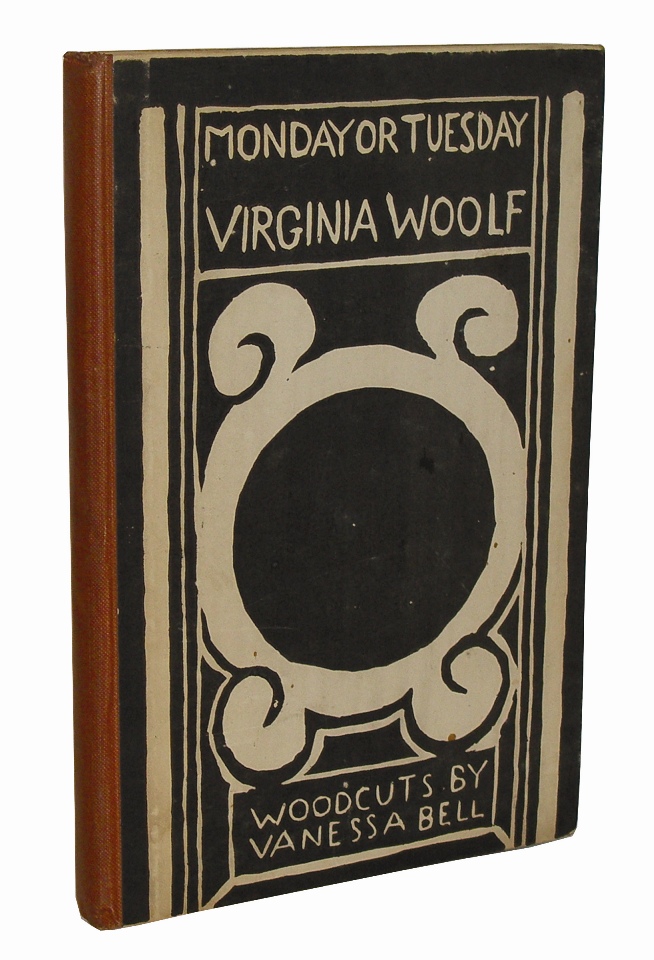

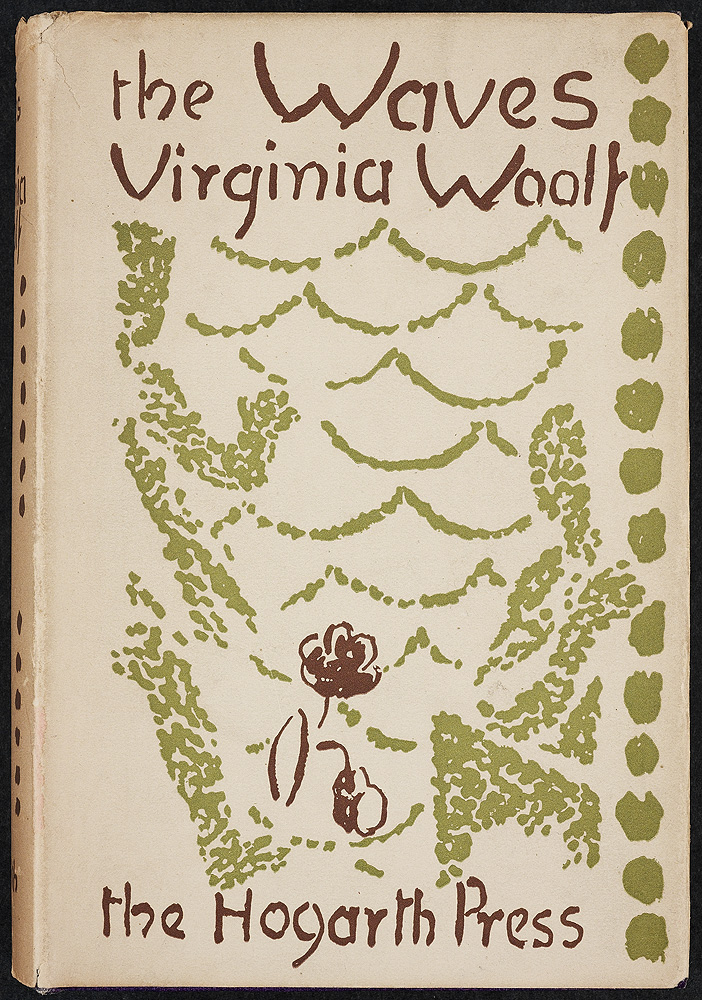

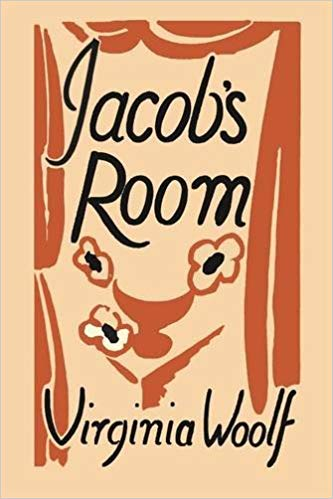

Today's profile is Virginia Woolf, whose work as a writer you are probably familiar with. But did you know she was also a printer?

Along with her partner Leonard, Woolf started the Hogarth Press in 1917. She retained her interest until 1938. While working at the press, the infinitely quotable Woolf once said "Real printing will devour one's entire life." (And yes, we have an infinite crush on her for many reasons including this one).

Leonard and Virginia printed more authors than we can list, doing bound editions of poets, essays, and retellings of Shakespeare. They even printed T.S. Eliot and E.M. Forster. But they were also invested in forwarding Virginia's career as a novelist. She printed her own Jacob's Room on the press in 1922, one of several titles they put out including Orlando, The Waves, and Monday or Tuesday.

These were some of the 527 titles they produced, according to Helen Southward's Leonard and Virginia Woolf, The Hogarth Press and the Networks of Modernism. The Hogarth Press became a node in a fascinating and important network of modernist literature, with Woolf at its center.

March 5

Today's profile is Henriette Avram, a programmer and analyst who created MARC (Machine Readable Cataloging) which changed modern librarianship. Avram's development of MARC involved translating bibliographic material into computer fields, which she completed at the Library of Congress. This project spanned her career, taking her from working alone to managing a department of several thousand. MARC records are the infrastructure of libraries. If you've used an online catalogue, you've interacted with MARC or a derivative. It automates certain parts of the job librarians used to do and facilitates sharing of data--its arguably most important contribution.

There are a lot of articles about Avram's work, covering not only her contributions to libraries but her early days as a programmer working for the NSA. She was not a librarian by trade, but referred to herself as happily "adopted" by the field.

Fewer people have had more of an impact on the way we think about books and how we share information. That's how much a system designer can shape thinking and how we categorize knowledge. Avram's MARC and the legacy of Avram herself will continue to quietly but pointedly shape our field.

March 6

Today's profile is on the Distaff Side, a feminist printing collective in the early twentieth century in the U.S. As they wrote in their 1937 Bookmaking on the Distaff Side, they are a: "loosely-knit organization of women enlisted from printing-offices, publishing houses, studios and other hiding-places where may be found devotees of the graphic arts. The group was born out of a righteous indignation that sufficient recognition had never been accorded to woman’s place in the history of printing. To amend this deficiency, The Distaff Side published its first book entitled Bookmaking on the Distaff Side."

If you can't tell yet why we love this book (and this group) they argued that there are "monumental contributions which spinsters, wives, and widows have made to the graphic arts." We are of the "not just wives and widows" group, but at the same time--SO MANY awesome widows! Here are a few looks at these women and their wonderful book.

March 7

Today's profile is the nuns of the press of San Jacopo di Ripoli, some of the earliest traces of women's labor in the European book trade. The nuns of the Ripoli press were an exception to modern expectations about what printing books in 15th century looked like. They printed hundreds of titles. They printed secular, as well as religious works. They were skilled laborers. And they were paid for their work. Like a lot of incunables (Latin for “from the cradle,” what we describe early books as), the books from the press included hand-added rubrication (red ink) and embellishments like headers that made them more closely resemble the decoration of manuscripts.

The Ripoli nuns' diario (daybook) has been transcribed with commentary by Melissa Conway, available under the title The Diario of the printing press of San Jacopo di Ripoli: 1476-1484: commentary and transcription. It includes more than 3,000 entries of the nuns' daily lives over eight years, and it's one of the richest sources we have about early printing.

The image is from this post from Naomi Nelson, which has more excellent photos of one of the books in the Duke archives, Incominciano Le uite de Pontefici et imperadori Romani.

March 8

Today's profile is Fanny Goldstein, librarian, bibliographer, and founder of Jewish Book Council in the United States. Another woman after our own heart like Dorothy Porter, Goldstein published bibliographies to educate the public and create a Jewish literary history--she grew the collections of the Boston Public Library to the second-largest holdings of Jewish literature and culture. Her bibliographies reached beyond Jewish literature and embraced a wide range of diverse immigrant cultures.

Goldstein worked at the Boston Public Library, and according to the Jewish Women's Archive, this experience made her believe that "knowledge of one’s own ethnic background—and that of one’s neighbors—was as important for successful acculturation as was knowledge of American language, job skills, and social customs." While a librarian in Boston, Goldstein founded such programs as Negro History Week, Jewish Music Month, Catholic Book Week, and Brotherhood Week.

She also started what is now the Jewish Book Council, which grants awards and sponsors Jewish Book Month in the U.S. The Association of Jewish Libraries has honored Goldstein by naming one of its awards the Fanny Goldstein Merit Award.

March 9

Today's profile is Avis G. Clarke, cataloguer and archivist at the American Antiquarian Society. The sheer volume of Clarke's labor, in cards at the AAS, is staggering. Clarke typed out index cards with printers' information on them in the Printers File in the AAS archives. The AAS writes that the file is "a masterpiece of indexing" that comprises 145 drawers of cards, quite the legacy of material labor to leave behind.

The Printers' File represents historical, biographical, bibliographical, and genealogical research on early printing in America, an extensive record of book trade labor before 1820. But it, like a lot else is imperfect and a reflection of biases in our historical record. Molly Hardy writes that the file includes four white cards labeled "Black Printers" that were a later addition from James Abajian who lamented the file's limitations. Hardy has more in this open access article.

Clarke's work was extensive and amazing. It lives on through digitization as modern bibliographers adapt it. Hardy writes that "Clarke was an indefatigable and, if rumors are true, somewhat eccentric workhorse whose output lasted a staggering forty-three years"

March 10

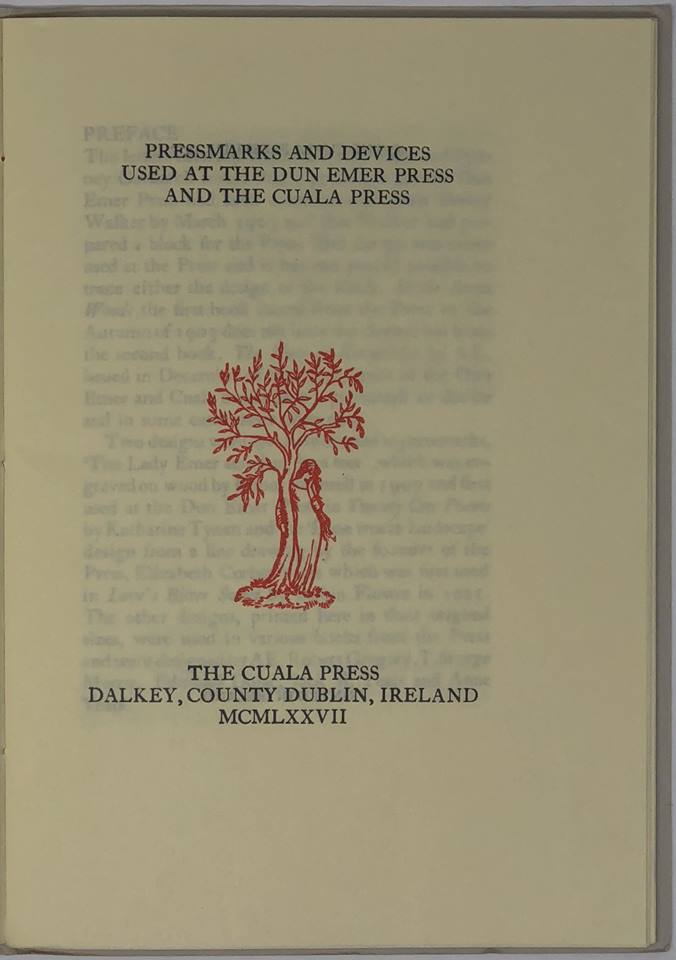

Today's profile is Elizabeth Yeats, an Irish printer who produced fine press books as part of a very talented family: her sister Lily was an embroiderer and her brother William was a poet. Along with Evelyn Gleeson, Lily and Elizabeth formed the Dun Emer Guild in Dublin, a women artisan collective that was part of the Arts and Crafts movement. The Yeats family had worked with William Morris, major figure in the movement, and his family while living in England. The Women's Museum of Ireland writes that the Dun Emer Guild's "designs were a rethinking of tradition, as it manifested itself in a country with a fractured colonial past. The translation of folk art became a basis for a national style."

Elizabeth formed the Dun Emer Press in 1902 as part of this collective, which she and Lily morphed into Cuala Industries in 1908. This was the only woman-run press during the arts and crafts period and remained so until it closed in 1946. Cuala Industries was never profitable, but it was a major force in the Celtic Revival that made truly beautiful books, gilded with fine linen paper and extreme care taken in design and typography. Elizabeth ran the printing, and they put out many of William's books of poetry. Their heirs donated their press to Mary Pollard at Trinity College Dublin.

March 11

Today's profile is Mary Simmons, a printer in seventeenth-century England who has intersections with an impressive number of literary writers and a stunning career. Mary Simmons's story is typically couched in those of her husband and her son (her biography is actually in theirs). They were John Milton's printers, with Matthew printing his political pamphlets and Samuel printing Paradise Lost. They get the scholarly articles and recognition while Mary... doesn't.

Mary printed from ca. 1656-1668, running the shop after Matthew died and until Samuel came of age. There are 34 imprints with her name on them, sometimes shared with her son. All while in the middle of a political, religious, and literary revolution. She operated the largest printing house in seventeenth-century London, with the 1666 Hearth Tax Roll noting that her shop had thirteen hearths, “a greater number than any other printer on the roll” (Plomer 164), and that she had two presses and eleven workmen (McKenzie 89).

Mary did not print any of Milton’s work, but she did publish several sermons and lectures by Joseph Caryl, a Puritan minister and sometime member of Oliver Cromwell’s entourage. After the Restoration of Charles II in 1660, Caryl was ejected from his church in London, but Mary kept printing his works.

Mary’s work in the family printing house thus locates her at the center a unique literary and political moment. Her success as a businesswoman during such dramatic times paints a fascinating portrait worth revisiting.

March 12

Today's profile is Mary Anne Everett Green, a historian, scholar, and editor in England in the nineteenth century who is a main reason the UK National Archives exist. Green was first known as a historian, and one who focused on women. She wrote two books: Letters of Royal and Illustrious Ladies and Lives of the Princesses of England: from the Norman Conquest. They were scholarly books, researched in private libraries and archives. Green's reputation as a historian earned her a position helping develop the the National Archives.

This was a notable achievement, because as Christine L. Kreuger writes, at the time, areas like history were being "professionalized" into male spaces like the university. Kreuger continues that Green complicates the narrative of professionalization as a process that excluded women. Instead, Green was highly valued. She worked with the Public Record Office (PRO) for 40 years, doing impeccable professional work: "she preeminently was responsible for defining the Calendars as a genre of historical writing." On top of doing essential historical work, Green was an early proponent for open-access records. She was one of three filers of a petition to let scholars access PRO records.

Some of Green's papers are held at the Bodleian Libraries for those who'd like to know more.

March 13

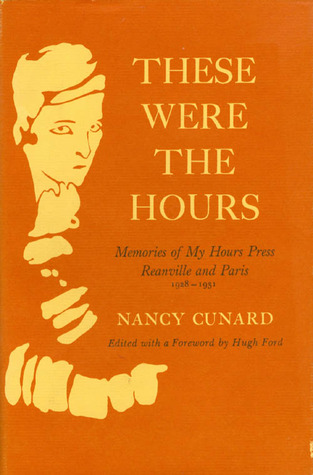

Today's profile is Nancy Cunard, twentieth-century author and activist, and her Hours Press, the fine press establishment she ran for many years in Paris. Cunard is a well known figure in the literary landscape , and her work at the Hours Press builds on her mythos. Hours Press was based in Paris, and Cunard printed all her work by hand, an artisan craft by the early 20th century.

The Hours Press's authors included Samuel Beckett, George Moore, Norman Douglas, Richard Aldington and Arthur Symons. All of her books were beautiful, fine press pieces of art that appreciated materiality as much as they brought to light important works of literature. Many of Cunard's books can be found online, like Negro Anthology here. But fine press books are always so much more fun in person. Princeton owns 18 out of 24 of the Hours Press books, so if you live on the East Coast live our dreams and go visit them.

For more on Cunard, check out Anne Chisholm’s biography or Shari Benstock’s Women of the Left Bank.

March 14

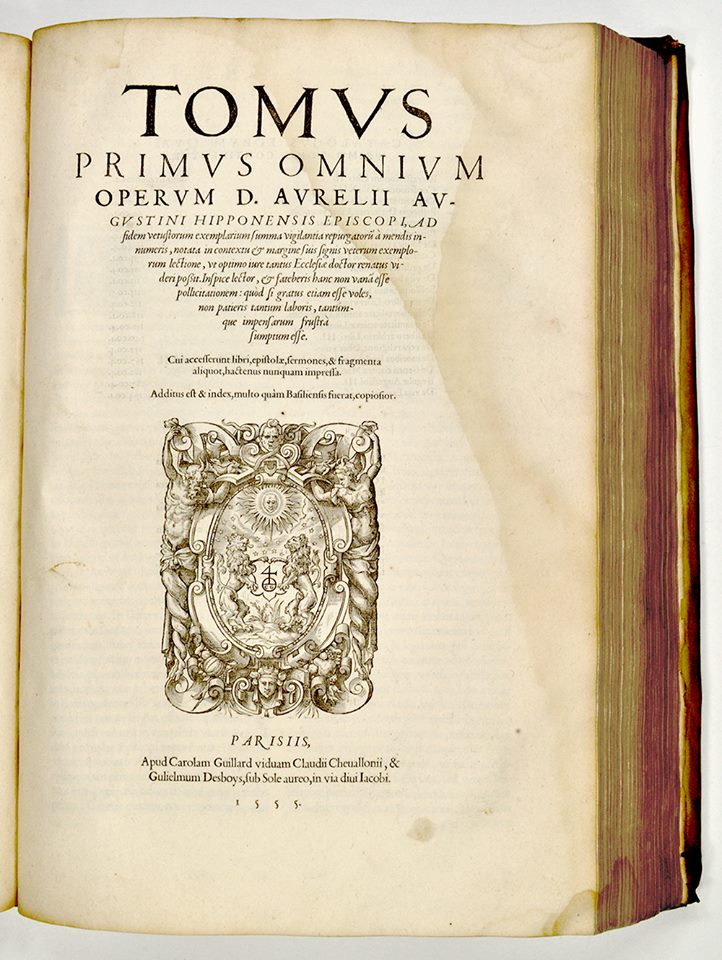

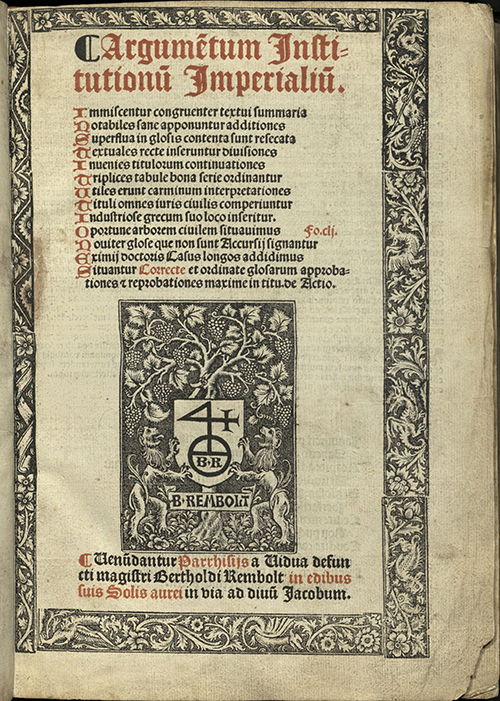

Today's profile is Charlotte Guillard, a sixteenth century printer in Paris. Guillard is sometimes identified as the first major woman printer, although we know of several others before her. She was twice married and widowed to printers; French guild law did not allow women to necessarily “own” their businesses, but they could continue to work. She ran a significant printing house, owning four or five printing presses with up to 25 employees as well as running a large bookshop. She also had a well-respected reputation both for aesthetics and for accuracy.

She proofread the Latin texts herself, creating editions valuable to the religious students who were her clientele. In fact, the Bishop of Verona specifically commissioned Guillard to publish his works, acknowledging that she had an international reputation.

Interestingly, although her second husband's name was Claude Chevallon, after his death Charlotte went back to her maiden name of Guillard on her imprints. However, she was still known as “Madame Chevallon” in the trade and throughout Paris. A significant number of her books also survive: According to Worldcat, more than 400 different libraries worldwide have books printed by Guillard. Pictured are books printed by Guillard at SMU and Yale.

March 15

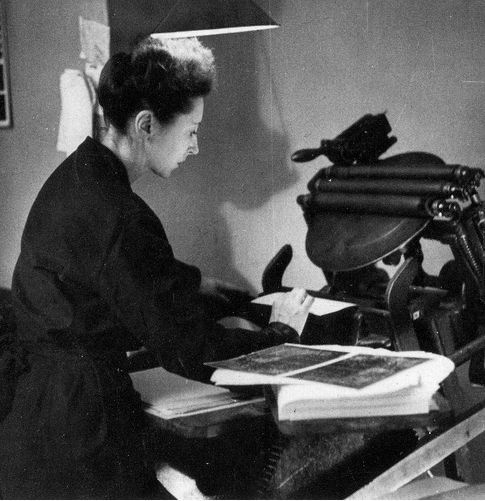

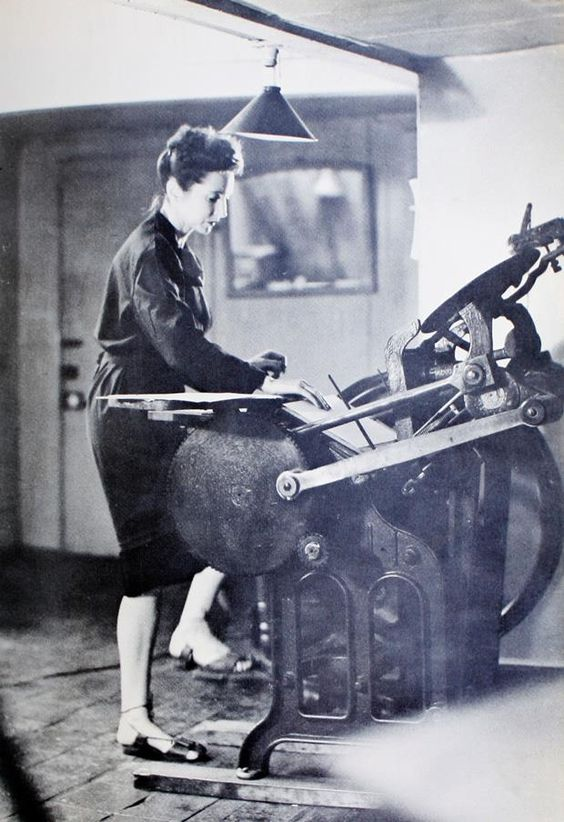

Today's profile is Anaïs Nin, author and printer. Perhaps best known as a prolific diarist and author of erotica, Nin ran Gemor Press from 1942-1947. After fleeing to America from the Nazi invasion of France, she was unable to find a publisher, so set up shop herself. Reflecting on printing in her diaries, she wrote:

"The relationship to handcraft is a beautiful one. You are related bodily to a solid block of metal letters, to the weight of the trays, to the adroitness of spacing, to the tempo and temper of the machine."

Gemor Press published over a dozen volumes of work by Nin and her circle of writer-artists, including Berhie Zilka, Bernardo Clariana, and Nin's lover Gonzalo More, for whom she initially bought their printing press. Nin's explicit writings were often heavily censored by her publishers. Unexpurgated editions were not published until the 1980s and 1990s, almost twenty years after her death.

Late in her life, the burgeoning feminist movement made Nin a popular figure, her writings revisited critically. However, little scholarship has been done appraising her work as a printer and publisher. We should revisit her career with those facets in mind.

March 16

Today's profile is Caresse Crosby, the "literary godmother to the Lost Generation." She also patented the modern bra. Go figure. First publishing their poetry as Editions Narcisse, Caresse and her then-husband Harry Crosby established Black Sun Press in 1927. They would publish early works by D.H. Lawrence, James Joyce, Ernest Hemingway, and Hart Crane, among others. After her husband's scandalous death (it may have been a murder-suicide) in 1929, Caresse continued publishing.

During WWII, she collaborated with Anaïs Nin (see above profile!) to publish an English translation of Ernst and Éluard's surrealist Misfortunes of the Immortals. As a brief side venture, she founded Crosby Continental Editions to publish paperback volumes by both European and American writers including Carl Jung, Dorothy Parker, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, and many others. It was unsuccessful and closed in 1933.

After WWII, Crosby founded Women Against War and tried with mixed success to establish a Center for World Peace. She also founded an artists' colony in Italy. Her political efforts have sadly received less attention than her work as a patron of the arts. Despite the cultural cache of the writers involved, Crosby and the Black Sun Press have received little literary attention, with too much credit going to Harry rather than Caresse.

March 17

Today's profile is Margaret B. Stillwell, a librarian and bibliographer who worked on incunables and had an exceptionally interesting career in the northeastern United States. Stillwell completed foundational bibliographic labor in the study of incunables (Latin for "from the cradle" which we call early printed books) with Incunabula and Americana, 1450-1800 and The Beginning of the World of Books, 1450-1470. These books became standard references for scholars of early print.

Stillwell worked for the The John Carter Brown Library, and the John Russell Bartlett Society has named the Stillwell Prize Ceremony for Undergraduate Book Collecting after her. This blog post from Emi Hastings has some compelling anecdotes about her working in freezing temperatures while at the Annmary Brown Memorial:

"The library had no heat or electricity in most of the building for the first ten years, and winter temperatures at Stillwell’s desk routinely dropped to as low as 44 degrees Fahrenheit. After years of pleading with the trustees, she finally had to threaten to resign if heat was not installed before the next winter. The trustees also refused to buy essential reference works, so Stillwell had to borrow them from friends at other libraries. In 1948, when the library was transferred to the management of Brown University, Stillwell was the first woman to be appointed to a full professorship on the University Faculty, although she never received a full professor’s salary."

Stillwell's remarkable career ended with her joining two clubs. She was the first honorary female member of the Grolier Club, a book-lover's association in New York. She was also a member of the Hroswitha Club, an association of women book collectors. More about the latter below!

March 18

Today's profile is Catherine A. Latimer, librarian at the New York Public Library in the early 20th century. She was the first African-American librarian at the NYPL. Latimer studied library sciences at Howard University, and she was hired at the NYPL's 135th Street branch in Harlem. Latimer's hire was motivated by the library's desire to build collections based on the local community, which was in the midst of the Harlem Renaissance.

As happens when one is the first of a new group, Latimer's letters reveal sustained tension to her presence even as the library seemed committed to integrating its staff. She complained she was passed over for promotions, at once point even moved away from the collection. Latimer's letters (and those about her) are digitized through the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. Here's one that lays out the difficulties of working within entrenched institutions when she was passed over for head of the Negro literature collection in favor of a white man.

One of Latimer's projects was a collaboration with Du Bois's Encyclopedia of the Negro. Latimer was responsible for the bibliography. She had connections with many of the major figures of the Harlem Renaissance and used these relationships to grow the NYPL collections.

March 19

Today's profile is 16th century English printer Jacqueline Vautrollier, one of the legion of wives and widows who somehow! ran businesses on their own. Like Mary Simmons (who we posted about on Mar. 11), Vautrollier is primarily known through her male relatives. Her first husband, Thomas, was a French printer who specialized in Protestant religious tracts and classics. Jacqueline briefly appears on his Wikipedia page. Similarly, Vautrollier appears on her second husband, Richard Field's page. It is assumed by these narratives that the printing in the shop then became Field's work. Even though she ran the shop during both husbands' lives and with the powerful legal autonomy of the widow!

This printing collective has come up for scholars of Shakespeare, as Field is listed as Shakespeare's printer for several pieces. But, we should remember not to position Jacqueline as the convenient vessel for passing property from Thomas to Richard. Vautrollier was a printer, too! She might have taught Field quite a bit when he was apprenticed to their firm. And she was probably a damn good businesswoman to keep a shop that large prospering alongside and independent of her husbands.

So today if you're having a moment while drinking your coffee, give up a toast to the wives and widows. They're rarely credited but form the foundational underpinning of the English print trade and so much more of our historical narratives.

March 20

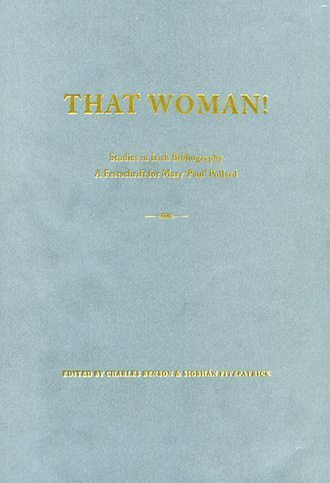

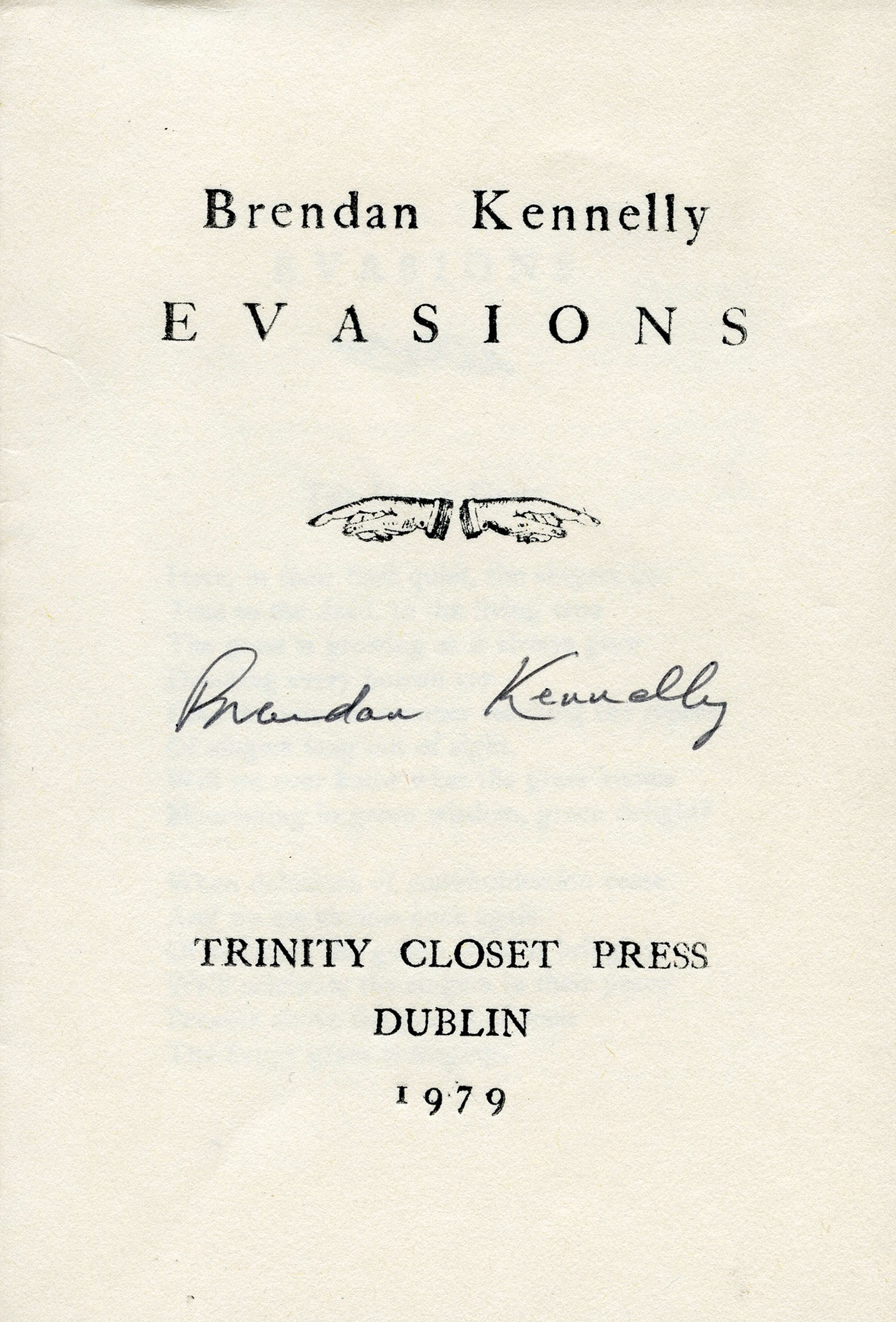

Today's profile is Mary "Paul" Pollard, Keeper of Early Printed Books at The Library of Trinity College Dublin. (Her title just makes us picture a menagerie of books with librarian zookeepers, and it is a delightful imaginary scene). Pollard profoundly affected the way Trinity approached its rare book collection. She taught historical bibliography, and she founded a pedagogical press called the "Trinity Closet Press." This press was the same Albion used by Elizabeth Yeats at Cuala from our Mar. 10 profile, which was donated by her family after the press closed down. This small but important imprint allowed TCD students to practice their handpress skills.

Pollard was also a foundational bibliographer in the field. While working at Trinity, she published Dublin’s Trade in Books, 1550–1800 (1989), and A Dictionary of Members of the Dublin Book Trade, 1550–1800 (2000). Both are indispensable for people working on early Irish printing.

She also collected thousands of children's books. They've been donated as the "Pollard Collection" and include: "items date from the 17th century to the early 20th century with a special focus on Irish imprints, Irish writers, and books written for girls." Pollard is perhaps best memorialized in the 2005 That Woman! – Studies in Irish Bibliography: A Festschrift for Mary ‘Paul’ Pollard and in the legacy she has left for those studying the Irish book trade. She was the first woman to hold the prestigious Lyell Readership in Bibliography and one of the few women to have done so at all (thanks to Leslie Howsam for this tip!).

March 21

Today's profile is Harriet Beardslee Prescott, who worked at Columbia University for 50 years, 40 of which she was head of cataloguing; she retired in 1939. During her tenure, Columbia increased its holdings from 100,000 to 1,400,000 volumes, and Prescott's cataloguing department made these items accessible to researcher and students.

On her excellent blog "Women in the Stacks," Jane Siegel writes that Prescott produced tens of thousands of new cards and altered half as many old ones, greatly increasing the usability of the card catalogue. Prescott's work came cheap, which is typical of women's labor (and cataloguing is still under-paid compared to other kinds of specialized work in libraries; honestly just pay all the librarians more). Siegel writes:

‘Harriet and the cataloging department had grown up alongside the modernized Columbia library, and Harriet was literally irreplaceable. At the time of her retirement, library director Charles Williamson wrote to President Butler: “I decided that there was no one in the Department who could be promoted to the position of supervisor of the entire department and also that the new administrative head ought under present conditions to be a man. I soon found, however, that no man with the essential qualifications was available at anything like Miss Prescott’s salary of $3500.” He had found a suitable man for the job, “but it would take at least $4500 to bring him to New York.” Instead, after her retirement, the Cataloging Department was split into three divisions, all three reporting to one (male) assistant librarian.’

We are indebted to the work of scholars like Siegel who bring these women's stories out of "the stacks" as it were. Much of this work has been on academic blogs--librarians saving and making available the histories of labor and scholarship at their own institutions. And that's why we can now hat tip to the great work of people like Prescott.

March 22

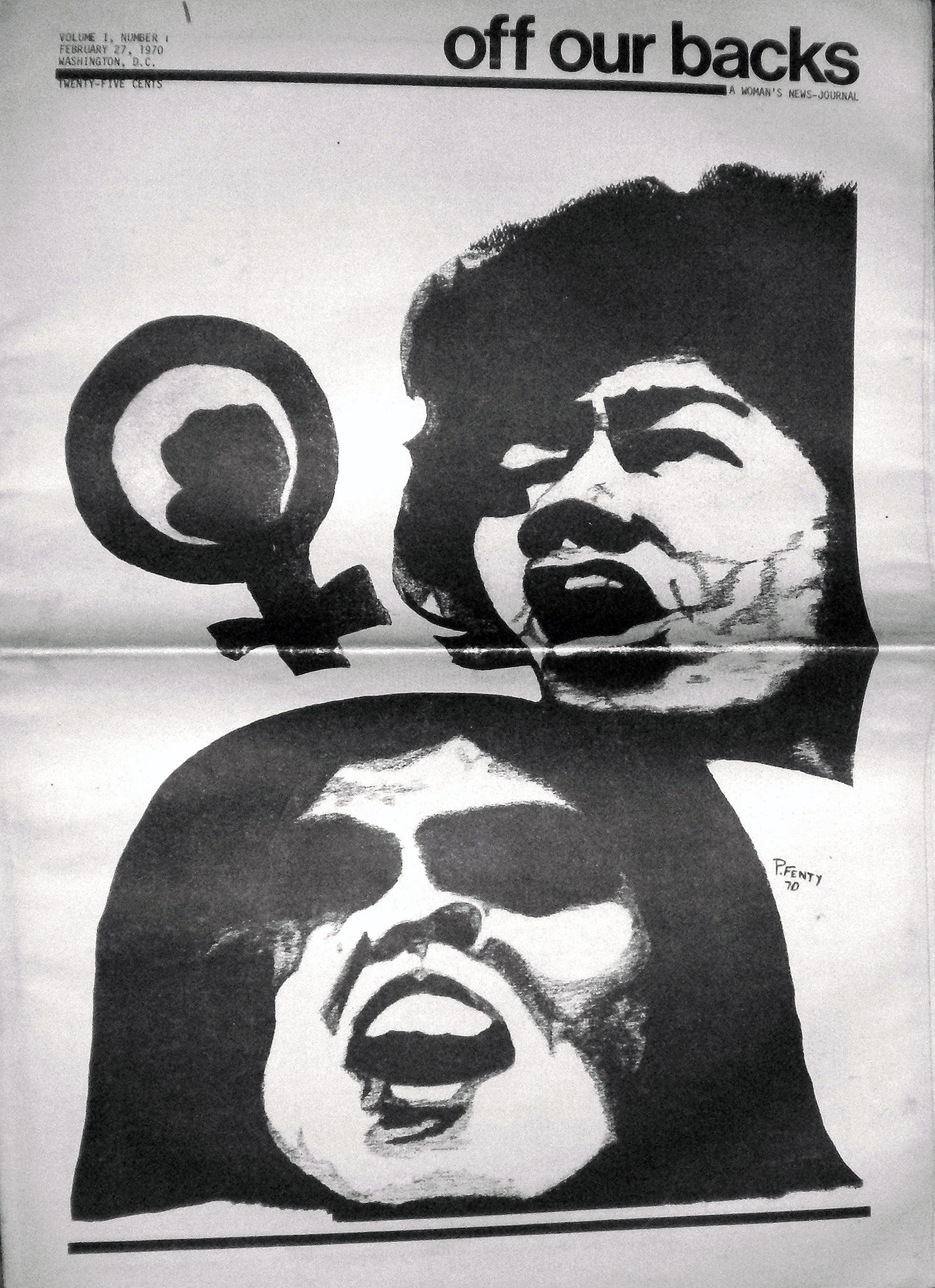

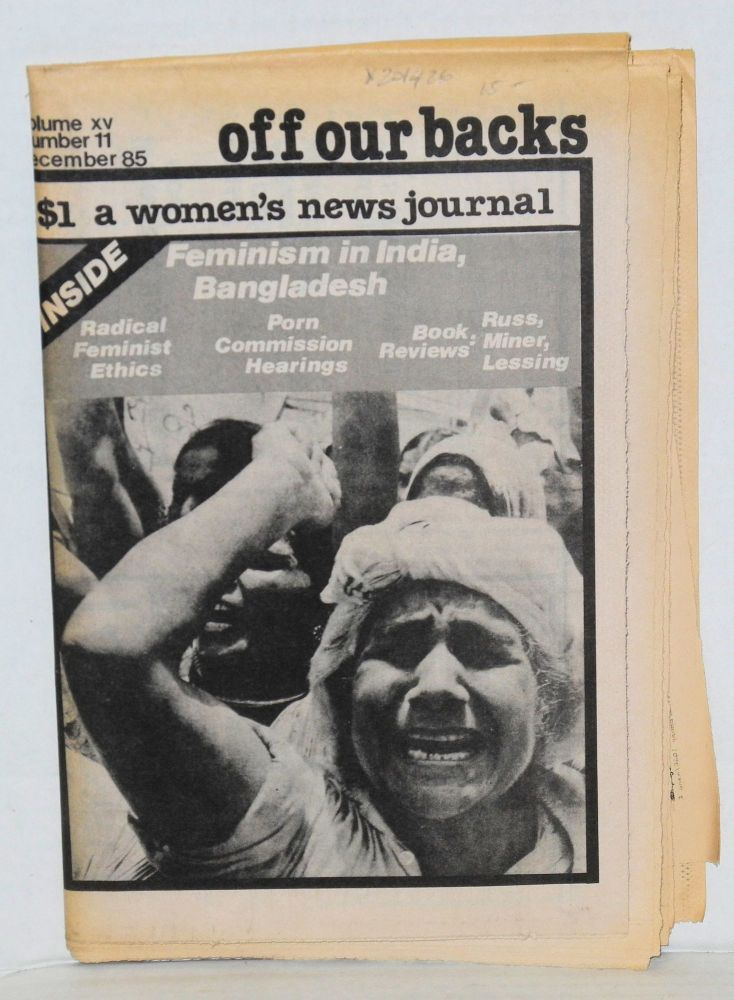

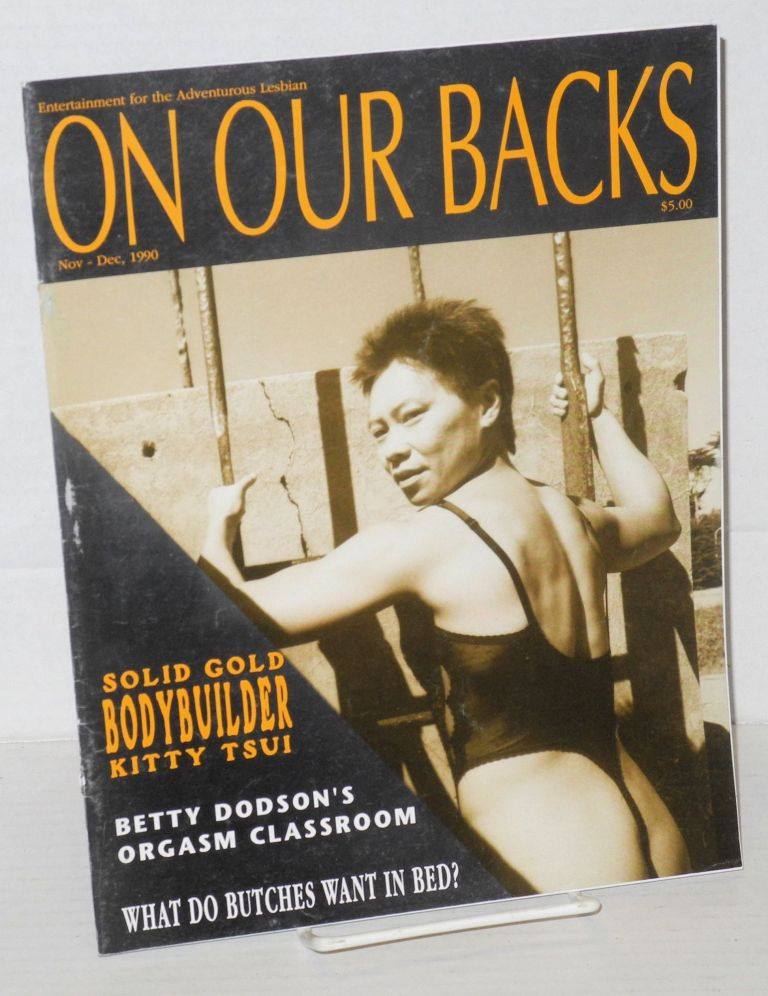

Today's profile is the newspaper Off Our Backs, affectionately called OOB, the longest continuously-running feminist journal. Published from 1970-2008, the journal was run by a feminist collective in which all decisions were made by consensus. OOB covered local, national, and international news pertaining to feminist, lesbian, and women's issues of the day. OOB's mission was to "to educate the public about the status of women around the world; to serve as a forum for feminist ideas and theory; to be an information resource on feminist, women's, and lesbian culture; and to seek social justice and equality for women worldwide."

In 1984, the first woman-run lesbian erotica magazine, On Our Backs, was founded, with its title intentionally satirizing that of OOB, which they found overly prudish. In turn, OOB regarded On Our Backs as "pseudo-feminist" and threatened legal action over the title and logo.

Never financially stable, OOB ceased publication in 2008, but it remains an important part of the feminist zine and periodical movement of the late 20th century. Some of its archives can be found at the University of Maryland. On Our Backs' archive is available at Brown University with a full run of the magazine and archive at Cornell University.

March 23

Today's profile is Katherine F. Pantzer, one of the most prominent women who worked in Anglo-American bibliography. She spent her long career at Houghton Library at Harvard University. Pantzer is best known for her revision of the English Short Title Catalogue (ESTC), an essential research tool for those working on English Early Modern printed books. The ESTC is a monumental affair; it lists most books we can find any record of with bibliographic information like year of publication and publisher.

Pantzer's work looks a lot like women's essential but unglamorous labor in libraries. David McKitterick writes that she inherited the project from William A. Jackson and worked in the basement with Janet E. Critics and Suellen Mutchow, turning dense notes into a legible project. Like most bibliographic projects, Pantzer battled haphazard funding and changing technologies. But the revision of the ESTC made our version of Early Modern publishing research fundamentally possible. As the ESTC is again revised, we still rely on Pantzer (and co.'s) labor.

By the end of the ESTC project, McKitterick writes that "her knowledge of the London book trade was, in many respects, verging on encyclopaedic." Fewer people in the 20th century have known more about the early printed book than Katherine F. Pantzer. The Bibliographical Society of America has several awards named after Pantzer, and the Houghton has a fellowship in her name.

March 24

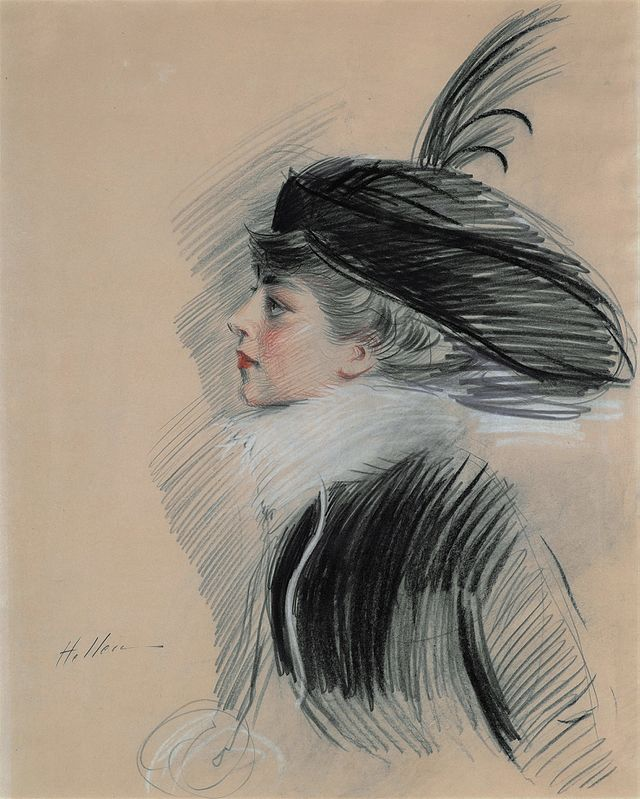

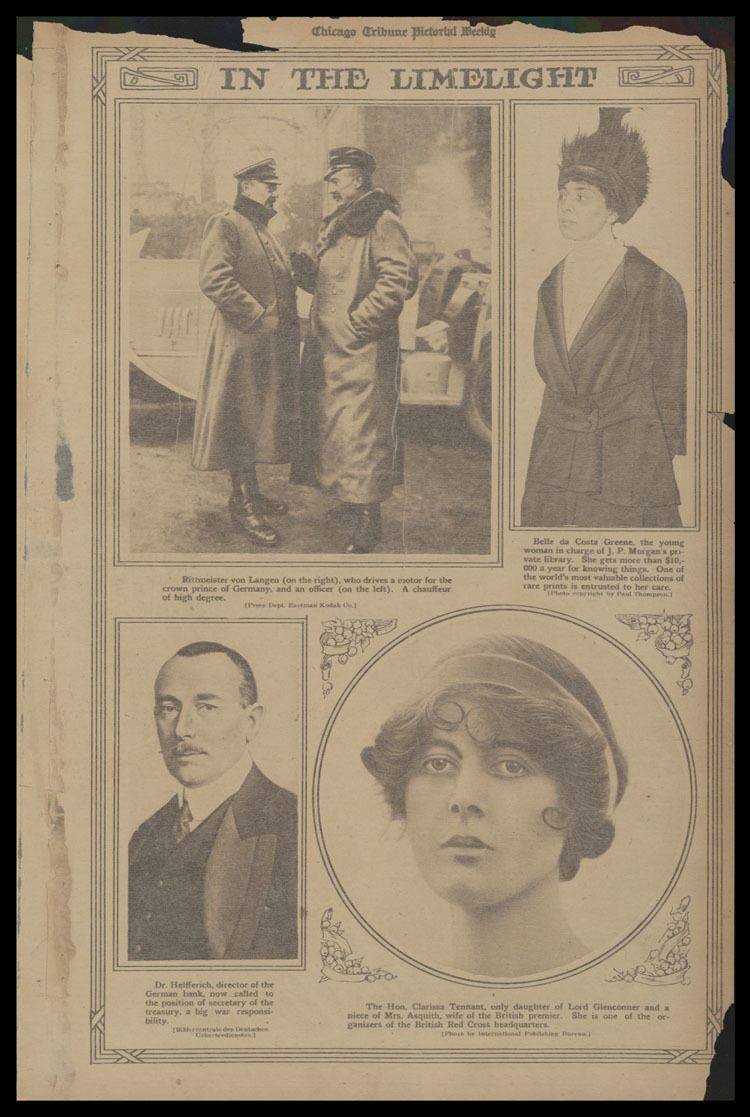

Today's profile is Belle da Costa Greene, first director of the the Morgan Library and socialite with an enviable sense of fashion. And really great hats. In Greene's biography An Illuminated Life, Heidi Ardizzone writes that Greene eschewed what librarians were "supposed" to dress and act like. Working for J.P. Morgan, one of the richest men in the world, gave her social mobility. Here's more:

"Belle knew that her chosen work as a librarian hardly fit the image and attitude that her flamboyant, mischievous soul demanded.* 'Just because I am a librarian ... doesn't mean I have to dress like one,' she reportedly boasted. And she didn't ... Nor did she perform her tasks quietly and demurely. Still, for most of her adult life, Belle oversaw Morgan's growing collection of rare books and art housed in his new building. Oddly kindred spirits, the two became partners in the acquisition of manuscripts and art"

Greene never married, and she also had to navigate her ancestry as she mixed with an increasingly diverse but still largely white social scene in 20th century New York. She was black but claimed Portuguese ancestry to make passing easier. Her lifestyle, while complex, has led to rather charming anecdotes for modern readers. Her biography notes that "if any male admirer attempted to follow up an evening flirtation by visiting her at the Library the next morning, he would quickly find himself back out in the street."

Social mobility also translated to renown. Ardizzone writes that Greene "reached a level of professional stature that few women of her generation were able to maintain." Her work turning the Morgan library into a renowned collection has had a lasting effect on archival scholarship.

*We would like to vouch that we know a LOT of flamboyant and mischievous-souled librarians, so hopefully some images have changed

March 25

Today's profile is Ruth Mortimer, cataloguer and bibliographer at the Houghton Library and Smith College, who has named its rare book room in her honor. To add to her legit creds, Mortimer was the first woman president of the The Bibliographical Society of America, and she edited PBSA. Her work in bibliography included reference works in 16th century Italian and French works, which became the standard in the field.

While at Smith, she increased the library's holdings of women writers like Plath and Woolf, early printed books, and fine press books. One her interests was Frankenstein, and she wrote a publishing history of the text and collected ephemera. The collection is preserved with its finding aid here.

While at Smith College, Mortimer focused on teaching the history of the book. From this work, we can see how Mortimer was instrumental in training a new generation of women bibliographers and book artisans, in addition to her legacy of preserving women's writing.

March 26

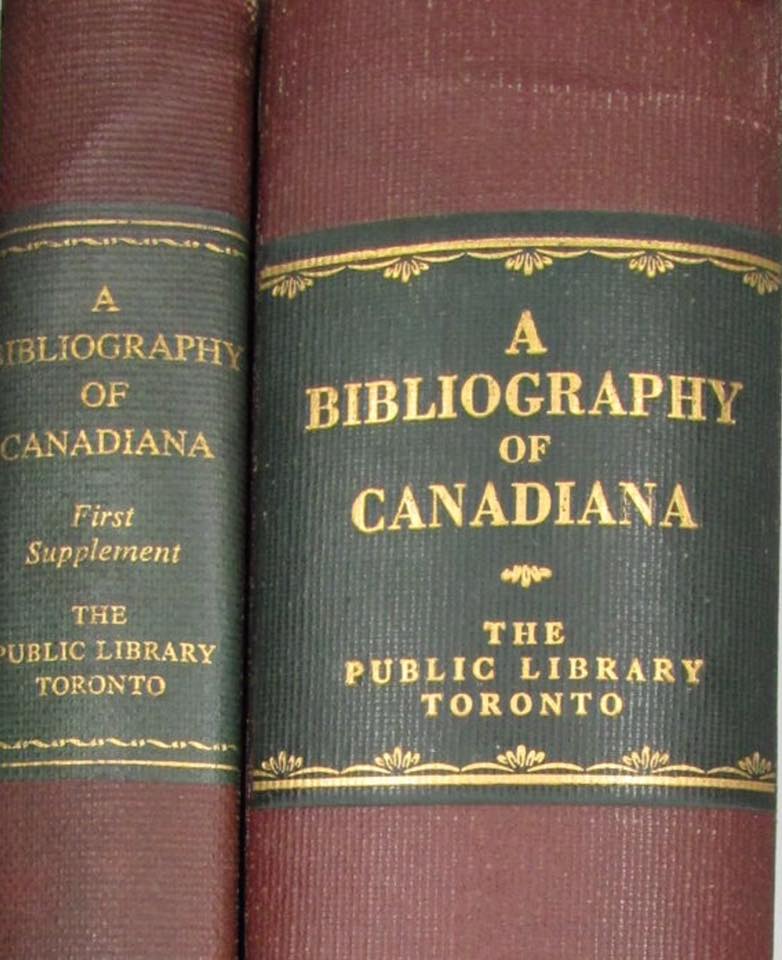

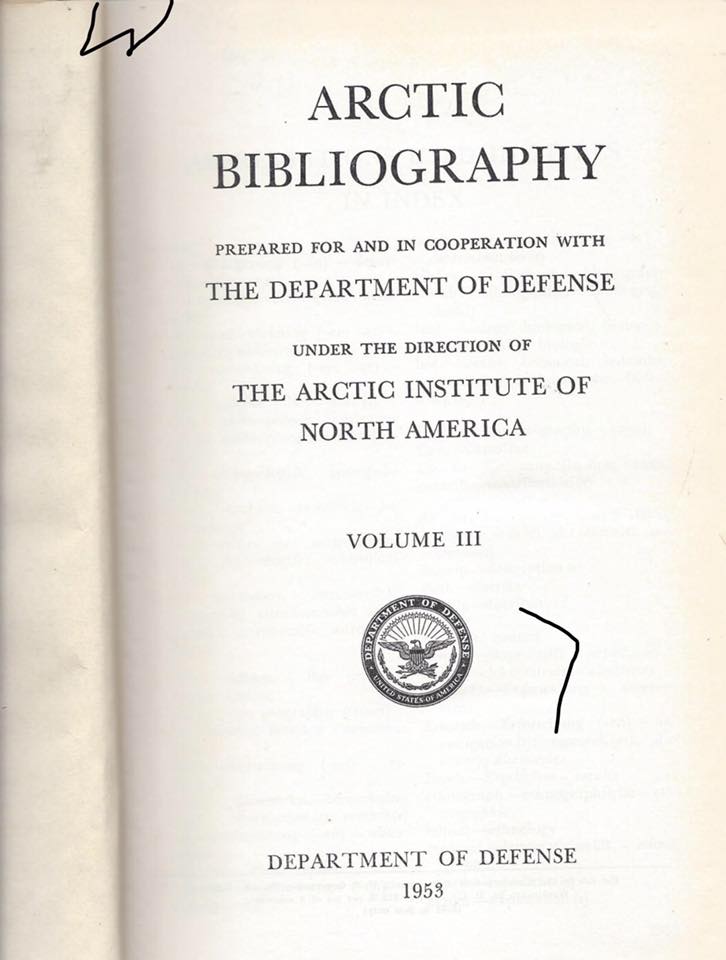

Today's profile is Marie Tremaine, "Canada's foremost bibliographer," who is remembered for her A Bibliography of Canadian Imprints: 1751-1800, A Bibliography of Canadiana, and Arctic Bibliography.

Tremaine's work on Canadian bibliography remains unparalleled. According to her obituary, she "personally searched the shelves of some 200 libraries across Canada and the United States to find 1204 monographs and pamphlets" published between 1751 and 1800. Her largest work was the Arctic Bibliography which encompassed 16 volumes, 14 of which Tremaine worked on personally. The massive work includes more than 20,000 titles of works related to the arctic, focusing on scientific and explorers' texts.

In her honor, the Bibliographical Society of Canada/La Société bibliographique du Canada has the Tremaine fellowship: "The Marie Tremaine Fellowship is offered in memory and through the generosity of Marie Tremaine (1902-1984), the doyenne of Canadian bibliographers. The Fellowship was instituted in 1987" which is available yearly.

March 27

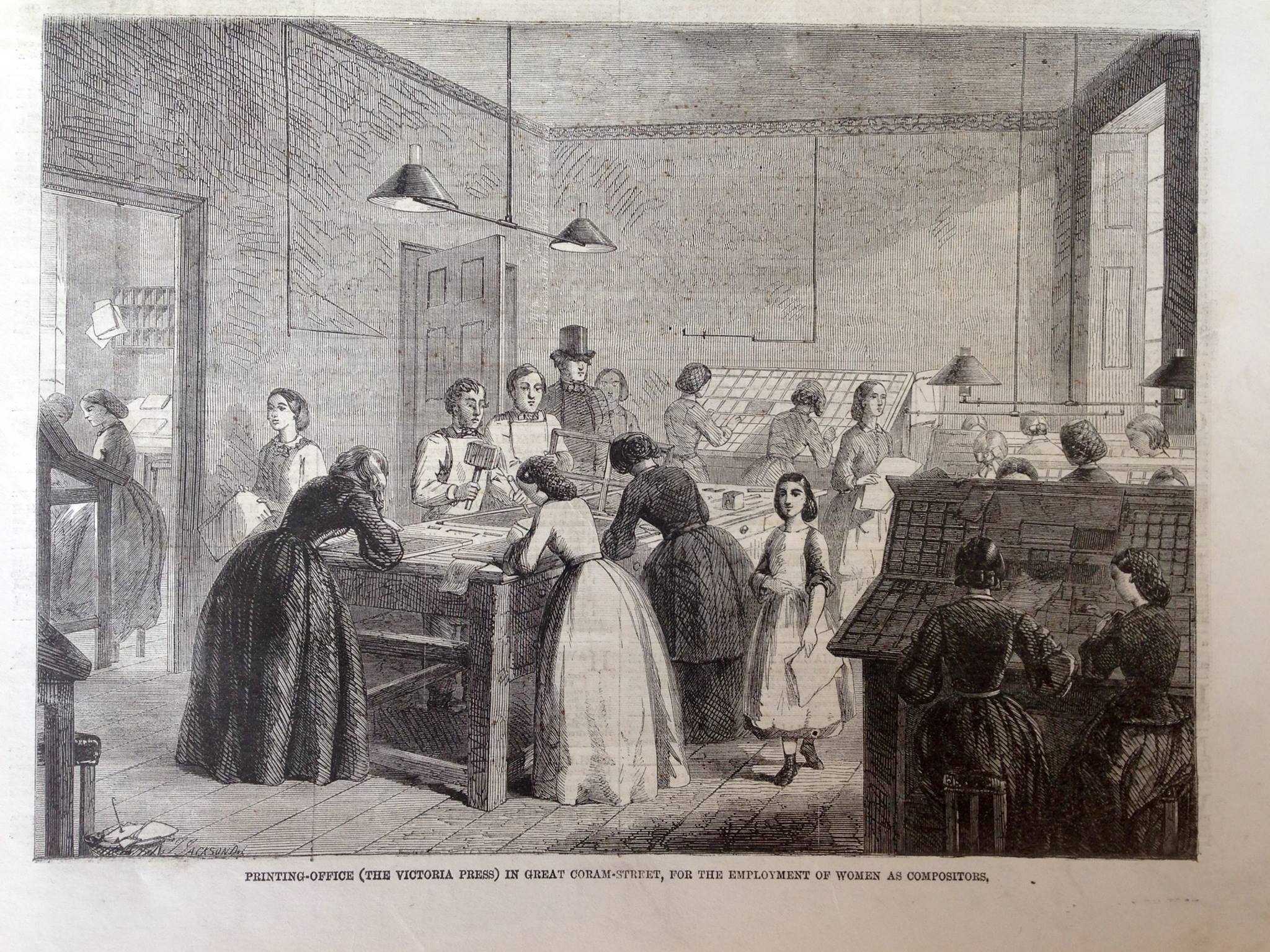

Today's profile is Emily Faithfull, founder of the feminist Victoria Press in Victorian England. She was a printer, writer, editor, and activist.

Nineteenth-century printing houses were terrible places to work, especially if you were a woman. Women who worked as paper feeders developed malformed backs; those cleaning type suffered miscarriages and stillborn/deformed babies from exposure to lead and toxic cleansers. Faithfull wanted to change the industry in England. Faithfull spent two years on a trip to America to visit the Women's Typographic Union in San Francisco. She would eventually write a book of observations from this and other trips called Three Visits to America (1884). An online edition is available here.

In 1860, she set up the Victoria Press, hiring women as typesetters. Perhaps not surprisingly, the London Printer's Union was Not Happy about this. She made a point of creating humane working conditions for her employees, including meal times and eight hour work days. Between 1860-1866 the Press published the English Woman's Journal, a proto-feminist magazine devoted to issues on employment for women. In 1863, she started the Victoria Magazine, which argued for fair pay for women, and ran it for 18 years.

Faithfull's archive is currently held at The Women's Library at the Library of the London School of Economics. Transcriptions are included in the finding aid here. You can also see more about the Victoria Press through the digital humanities project Victoria Press Circle, run by Miranda Marraccini.

March 28

Today's profile is Lillian H. Smith, a children's librarian who pioneered a new classification system for children's books. The Lillian H. Smith Branch of the Toronto Public Library is named in her honor. In Pioneers and Leaders in Library Services to Youth, Marilyn Lea Miller writes that Smith was the first children's librarian with academic credentials in librarianship in the British Empire. She worked at Toronto Public Library from 1912 until 1952.

Smith's work developing children's book collections in Canada extended beyond the library. Miller writes that Smith organized the "Boys and Girls Work Congress" which brought together a community of organizations focused on childhood development and wellness. Her history at TPL details that "By the end of her 40 years of innovative leadership, children's services were available in 16 branch libraries, 30 schools and two settlement houses, as well as at the flagship Boys and Girls House, opened on St. George Street in 1922." The Toronto Public Library has more on her as well.

Smith also taught, serving as a professor at the University of Toronto Library Sciences school for years. Madge Alto writes that she was "presented" to Smith, glass of scotch in hand, by other librarians who had her as a professor. She trained an entire generation of librarians.

Smith's legacy has been memorialized in the 1990 Scarecrow press festschrift Lands of Pleasure: Essays on Lillian H. Smith and the Development of Children's Libraries edited by Adele M. Fasick, Margaret Johnston, and Ruth Osler. And we'll leave you with one of our favorite quotes:

"Good children's books give those who enjoy them a steadying power, like a sheet anchor in a high wind, not moral at all, but something to hold to."

March 29

Today's profile is the Hroswitha Club, a women book collectors and bibliophiles club that lasted from 1944 to 1999. Hroswitha's members included Belle da Costa Greene (Mar. 24 profile), Margaret B. Stillwell (Mar. 17 profile), Sarah Gildersleeve Fife, Frances Hooper, and Henrietta C. Bartlett. They were a mixture of scholars, collectors, socialites, and librarians. The Hroswitha Club formed because they could not be admitted to the Grolier Club. Many members of Hroswitha were affiliated with Grolier, including Stillwell and Ruth S. Grannis, the Grolier librarian.

Book collecting, like academia, has long been antagonistic or inhospitable to women collectors. In her blog "Women Collectors in Their Own Words," Emi Hastings details the reasons that women collect, and what "counts" as collecting through women collectors memoirs. In an address to Hroswitha, Miriam Y. Holden writes "We have all of us learned that the collecting instinct can be a most rewarding source of pleasure and satisfaction for the collector, regardless of the fact that no collection is ever complete or ever perfect." She continues:

"What nobody still seems to know about woman, even at this mid-point of the twentieth century, is the reality of her historic meaning as a potent agent, in creating the patterns of society which are known to history. To reveal woman’s part in the making of long history, is the purpose of my library. I am trying to collect and make available to historians, students, and writers, the records of Woman’s Role in Civilization and show what her political and legal and economic status in various centuries and countries was, and what progress she was able to make in education, science, culture, and religions."

The Hroswitha Wikipedia page was just saved from deletion this week. It's a good a time as ever to return to this exciting group of women book collectors and curators, each of which deserves her own profile.

March 30

Today's profile is Lydia Bailey, a Philadelphia printer from 1808 to 1861 who is sometimes called “the last of the widow printers.” Her husband was a struggling printer who died in 1808, leaving her massively in debt and with several children to support. Within years, she singlehandedly transformed a flagging business into a major printing company.

By 1813, Bailey became the official city printer for Philadelphia, a position she held for over forty years, and she acquired significant job printing contracts with the University of Pennsylvania and a number of private companies. During her career she saw major shifts in printing technology as hand-press work shifted to automated, steam-powered presses that produced greater numbers of work for lower cost, but she never embraced that technology. However, her shop remained one of the largest in the city. She employed some forty workers, and she trained her son to be her successor but he never fully took on the business. When she eventually retired after five decades in the trade, she simply closed her shop.

Lydia Bailey is one of the most significant printers in American history. In 2013, Karen Nipps published Lydia Bailey: A Checklist of Her Imprints, which is well worth checking out.

March 31

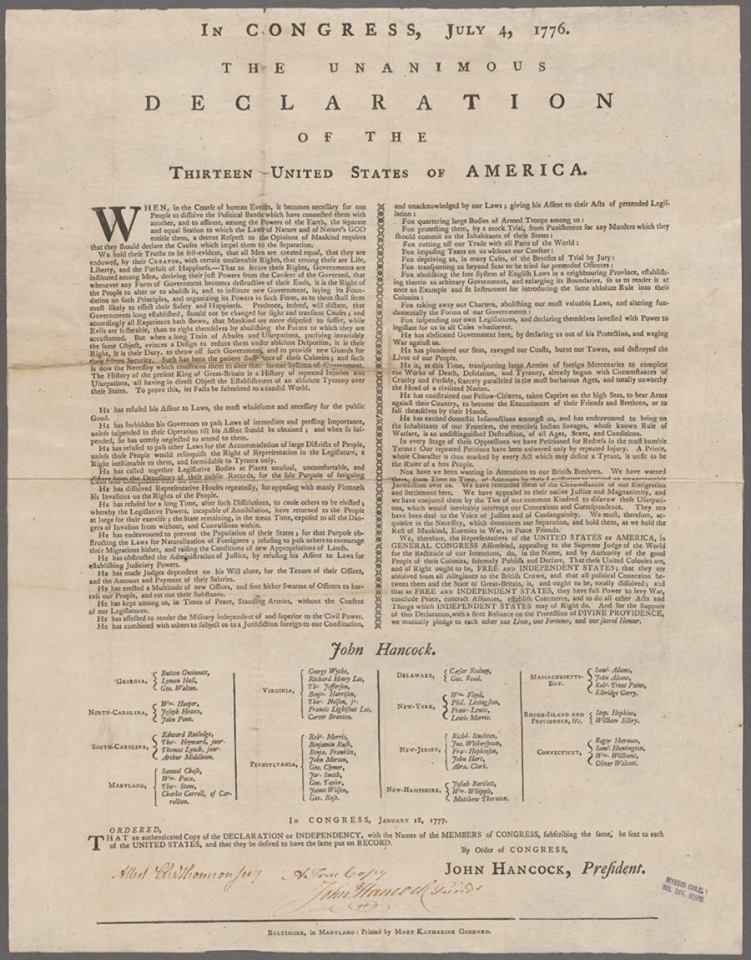

Today's profile is Mary Katherine Goddard, publisher of the Declaration of Independence, and the first to include the names of all the signatories. Goddard was the daughter of a family of printers, including the first to print a newspaper in Rhode Island, the Providence Gazette. Her brother William founded the pro-revolution Maryland Journal, which Goddard took control of in 1774.

In 1775, Goddard became the postmaster of Baltimore and held the position throughout the war. She vehemently opposed the Stamp Act, published an almanack, and ran a small bookstore. Girl had mad skillz.

In 1777, the Continental Congress moved to widely distribute the Declaration of Independence. Goddard was among the first to offer her press for the job, and so published what became known as the Goddard Broadside of the Declaration. After the war, Goddard continued work as postmaster, printer, and bookseller. However, in 1789, after 14 years, she was forced out of her job of postmaster as the Postmaster General declared the position required "more traveling ... than a woman could undertake."

Despite community protest, Goddard "retired" from the position and turned to printing and bookselling full time, dying in 1816. Her reputation has seen a resurgence in recent years, with annual articles appearing summarizing her legacy... on July 4.

Want more Sammelband?

-

October 2022

- Oct 16, 2022 Teaching in the Maker Studio Part Two: Safety Training and Open Making Oct 16, 2022

- Oct 16, 2022 Teaching Book Forms Oct 16, 2022

- Oct 16, 2022 Teaching Letterpress with the Bookbeetle Press Oct 16, 2022

-

September 2022

- Sep 24, 2022 Making a Scriptorium, or, Writing with Quills Part Two Sep 24, 2022

- Sep 16, 2022 Teaching Cuneiform Sep 16, 2022

- Sep 4, 2022 We're Back! Teaching Technologies of Writing Sep 4, 2022

-

June 2020

- Jun 1, 2020 Black Lives Matter Jun 1, 2020

-

May 2020

- May 1, 2020 The Special Collections Classroom in the Time of Covid-19 May 1, 2020

-

April 2020

- Apr 1, 2020 Teaching Materiality with Virtual Instruction Apr 1, 2020

-

March 2020

- Mar 1, 2020 Teaching Manuscript: Lessons Learned From Quill-Cutting Mar 1, 2020

-

February 2020

- Feb 1, 2020 Making the Syllabus Zine Feb 1, 2020

-

January 2020

- Jan 1, 2020 Teaching Print History with Popular Culture Jan 1, 2020

-

December 2019

- Dec 1, 2019 Teaching with Enumerative Bibliography Dec 1, 2019

-

November 2019

- Nov 1, 2019 Finding Women in the Historical Record Nov 1, 2019

-

October 2019

- Oct 1, 2019 Teaching in the Maker Studio Oct 1, 2019

-

September 2019

- Sep 1, 2019 Graduate School: The MLS and the PhD Sep 1, 2019

-

August 2019

- Aug 1, 2019 Research Trips: Workflow with Primary Documents Aug 1, 2019

-

July 2019

- Jul 1, 2019 Research Trips: A Beginner's Guide Jul 1, 2019

-

June 2019

- Jun 1, 2019 Building a Letterpress Reference Library Jun 1, 2019

-

May 2019

- May 1, 2019 Teaching Manuscript: Writing with Quills May 1, 2019

-

April 2019

- Apr 1, 2019 Why It Matters: Teaching Women Bibliographers Apr 1, 2019

-

March 2019

- Mar 1, 2019 What does it mean to teach a feminist book history? Mar 1, 2019

-

February 2019

- Feb 1, 2019 Roundup of Materials: Teaching Book History Feb 1, 2019

-

January 2019

- Jan 1, 2019 Building and Displaying a Teaching Collection Jan 1, 2019

-

December 2018

- Dec 1, 2018 Critical Making and Accessibility Dec 1, 2018

-

November 2018

- Nov 1, 2018 Teaching Bibliographic Format Nov 1, 2018

-

October 2018

- Oct 1, 2018 Teaching Book History Alongside Literary Theory Oct 1, 2018

-

September 2018

- Sep 1, 2018 Teaching with Letterpress Sep 1, 2018

-

August 2018

- Aug 1, 2018 Teaching Manuscript: Circulation Aug 1, 2018

-

July 2018

- Jul 1, 2018 Setting Up a Print Shop Jul 1, 2018

-

May 2018

- May 1, 2018 Teaching Manuscript: Commonplace Books May 1, 2018

-

April 2018

- Apr 1, 2018 Getting a Press Apr 1, 2018

-

March 2018

- Mar 1, 2018 Teaching Ephemera: Pamphlet Binding Mar 1, 2018

-

February 2018

- Feb 1, 2018 Empirical Bibliography: What It Is and Why It Matters Feb 1, 2018

- Feb 1, 2018 Introducing Sammelband: A Book History Pedagogy Blog Feb 1, 2018